Creativity Marked by Playful Imagination

Miroslav Šutej is an idiosyncratic personality on the Croatian and international printmaking scene; his mobile serigraphs are the most inventive segment of his work and an authentic contribution to graphic arts. Still today, Šutej’s prints enthral and excite an engaged spectator’s imagination. They are characterised by abstract geometry poetics, the vibrancy of a vivid colour scheme, visual effects, allusive ambiguity, playful serenity and complex variabilities. What makes Šutej still topical and his works permanently inspiring is his particular creative approach and playful interpretative freedom which turns graphic arts into a field of innovation and a place of imagination acknowledgment. Šutej’s artistic originality, as summarised by Ješa Denegri and Ive Šimat Banov, stems from the capability of seeking “(…) a place for imagination where it seemed not necessary anymore to most people,” i.e. “turning ordinariness into a sensation, off-the-rack items into fantasy.”

Miroslav Šutej is an idiosyncratic personality on the Croatian and international printmaking scene; his mobile serigraphs are the most inventive segment of his work and an authentic contribution to graphic arts. Still today, Šutej’s prints enthral and excite an engaged spectator’s imagination. They are characterised by abstract geometry poetics, the vibrancy of a vivid colour scheme, visual effects, allusive ambiguity, playful serenity and complex variabilities.

What makes Šutej still topical and his works permanently inspiring is his particular creative approach and playful interpretative freedom which turns graphic arts into a field of innovation and a place of imagination acknowledgment. Šutej’s artistic originality, as summarised by Ješa Denegri and Ive Šimat Banov, stems from the capability of seeking “(…) a place for imagination where it seemed not necessary anymore to most people,” [1] i.e. “turning ordinariness into a sensation, off-the-rack items into fantasy.” [2]

Miroslav Šutej’s artistic activity is related in art history to the New Tendencies (1961-1973), the international movement launched in Zagreb in 1961 and the visual phenomenon called the Zagreb Serigraphy, [3] and his art belongs to the field of the 1960s ‘new visuality’. [4] This prevalently neo-constructivist movement, representing in Croatia a new creative upswing of abstract art, a re-actualisation of Exat’s postulates and aesthetics and the empowering of new visual explorations, would earn Šutej international presence and visibility, while the New Tendencies’ principles will provide him with basic creative guidelines. Although he did take part in the movement’s exhibitions, first in 1963, yet again in 1969 and 1973, and was well-acquainted with their thematic scope, Šutej did not fully adopt all the principles, nor was he ever part of the founding structure, whose participants included the Exat members Vjenceslav Richter, Ivan Picelj and Aleksandar Srnec – creative notables whose work, among others, made a significant impact on the young artist. [5]

The reasons for that can be sought in his peculiar autonomy and immense imagination, as well as in a traditional formal formative orientation, acquired at the Academy of Fine Arts under professor Marijan Detoni (1956-1961), followed by Krsto Hegedušić’s masterclass (1961-1963). His initial visual efforts are characterised by traditional graphic techniques, such as aquatint and etching, drypoint, lithography and woodcut, as well as figurative motifs in which the real original is barely recognisable. [6] They were made in the late 1950s, a heterogenous stylistic period dominated by Art Informel and similar phenomena, as well as complex general events in art leading to a gradual, as Vera Horvat Pintarić detects it, “internationalisation of style on the outskirts way off centre“ [7]. In this period, prerequisites for a future pervasion of quite a new artistic spirit and visual preoccupations gradually took form, seeking new ways of portraying the world in the wake of geometric abstraction, most succinctly outlined by Ješa Denegri: “In the country, the atmosphere of inclination to constructivist art ideas are kept awake by rare exhibitions (the Bloc-Pillet-Vasarely serigraphs in Zagreb’s Gallery of Contemporary Art in 1957), however the atmosphere is most evidently fostered by Man and Space, whose editor-in-chief is Vjenceslav Richter since 1959. [In] 1959-1960 this magazine publishes translations of Seuphor [Michel Seuphor, Abstract Art, translated by Radoslav Putar], Vasarely, Max Bill, Anthony Jill etc., it writes about Malevich, Mondrian, Ben Nicholson, concrete art; for the very first time in our country Argan is translated and one text by Guy Habasque speaks about the artistic situation ‘beyond Informel painting’.“ [8]

The young artist, attracted by the new artistic trends, very quickly sided with the New Tendencies’ creative current and started to evolve within the scope of the new practices of geometric abstraction, however keeping some chosen qualities of the previously acquired artistic experience. In a little less than two years between his graduation (1961) and his first solo exhibition at the Student Centre in Zagreb (1962), Šutej fully defined his visual expression. Relying on the adopted, as well as on the preferences of his own, he embraced new visual exploration and the spirit of non-conformism which inherently challenged the traditions and conventions, i.e. he severed the ties with tradition and denied the auraticity of a work of art and its maker. However, as Zvonko Maković noticed, “he never literally embraced exactness and scientific strictness, preached by New Tendencies theorists.“ [9]. In quite a personal iconic narrative, elements of shock, estrangement and imagination are preserved, as traces of surrealism and a detachment from absolute order, as well as relativisation of the abstract favouring allusive micro-figuration of the objective. Free from any narrativity and descriptiveness, Šutej’s artistic interpretation of the micro-world is a creative coil of both wondrous and exact, bizarre and geometric, humorous and provocative, free and rigorous, order and dis-order. The duality of his iconicity is interpreted among the first people by Vera Horvat Pintarić – an outstanding connoisseur and apologist of Šutej’s art, [10] followed by Zvonko Maković, Ješa Denegri, Andrej Smrekar and others, all attributing such iconic aspects to the power of Šutej’s imagination, while Tonko Maroević ‘concludes’ (in the catalogue of Šutej’s last exhibition in 2005): “We are convinced that the ‘spice’ of human character, or at least a mimetically underlined physical attribution (arm, eye, head, genitals), stimulates an emphatically more intense ‘reading’ and interpretation of sculptural facts.“ [11]

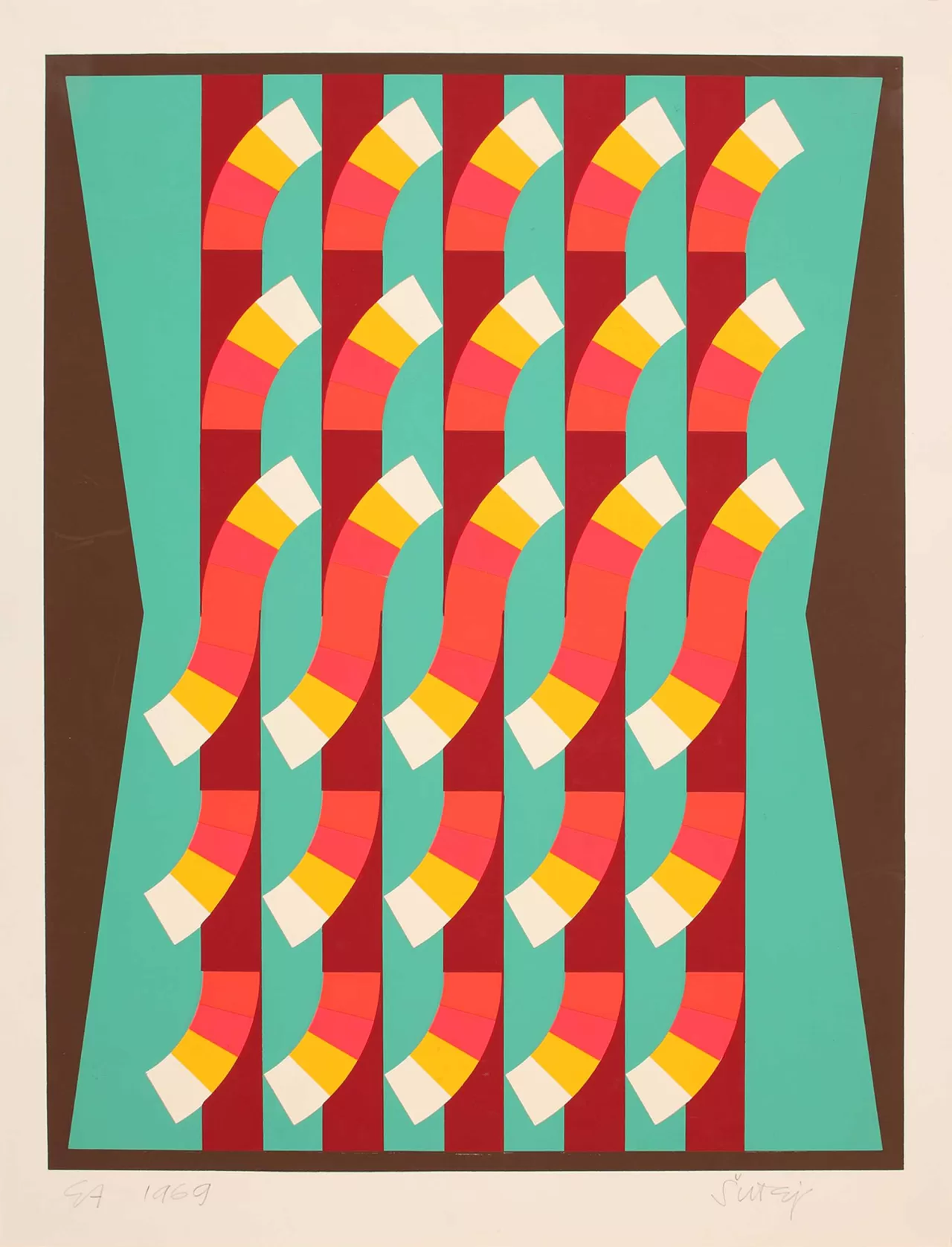

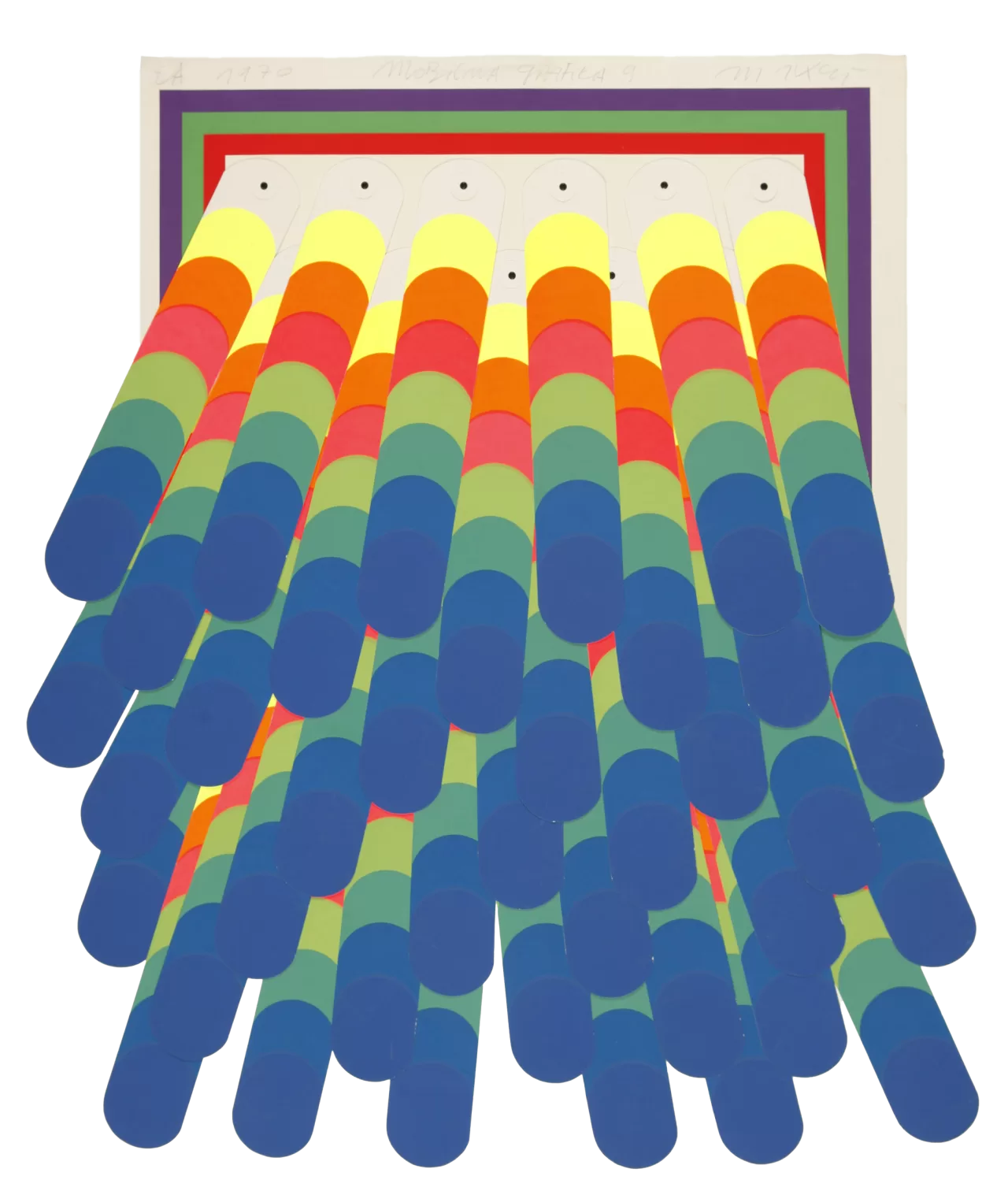

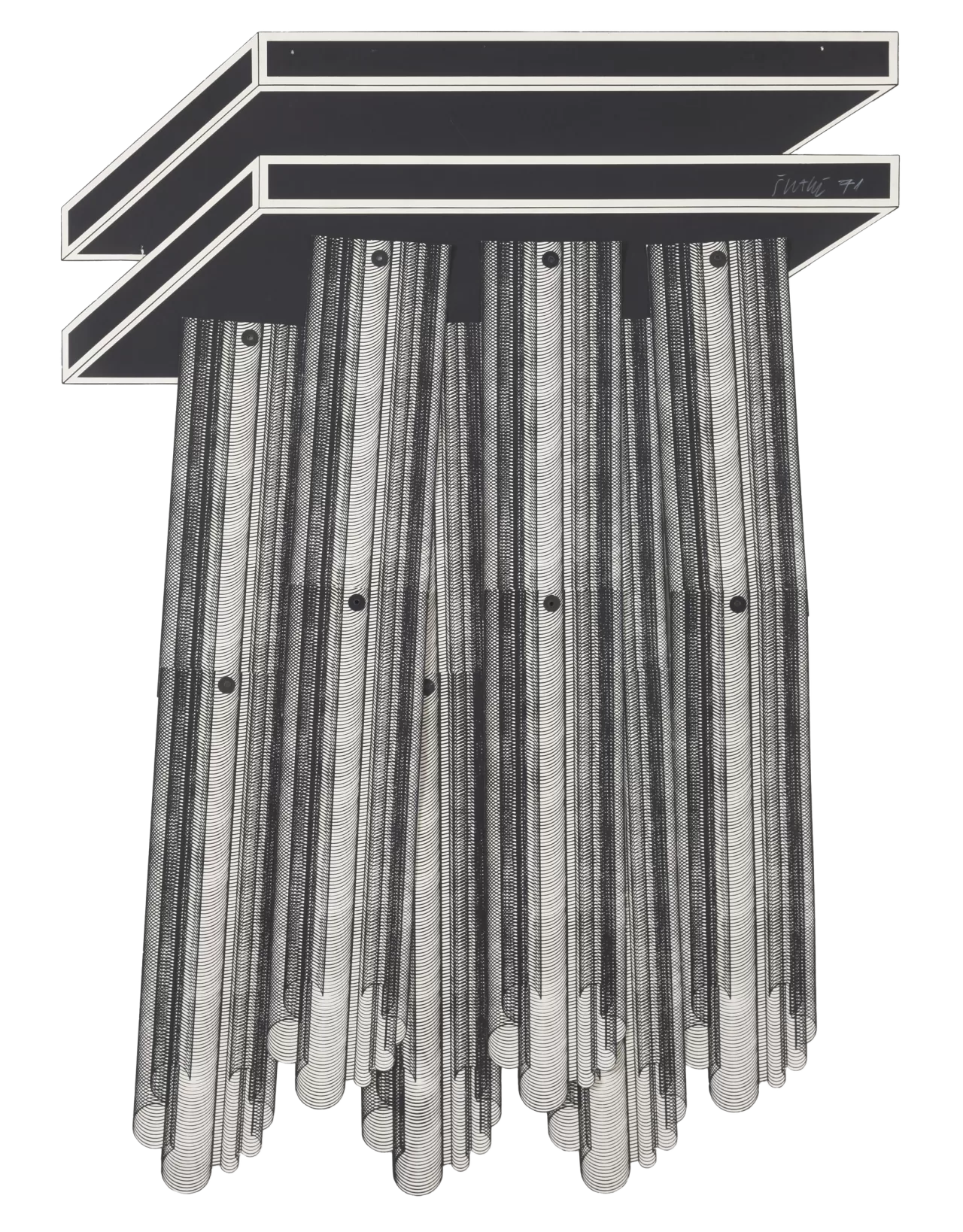

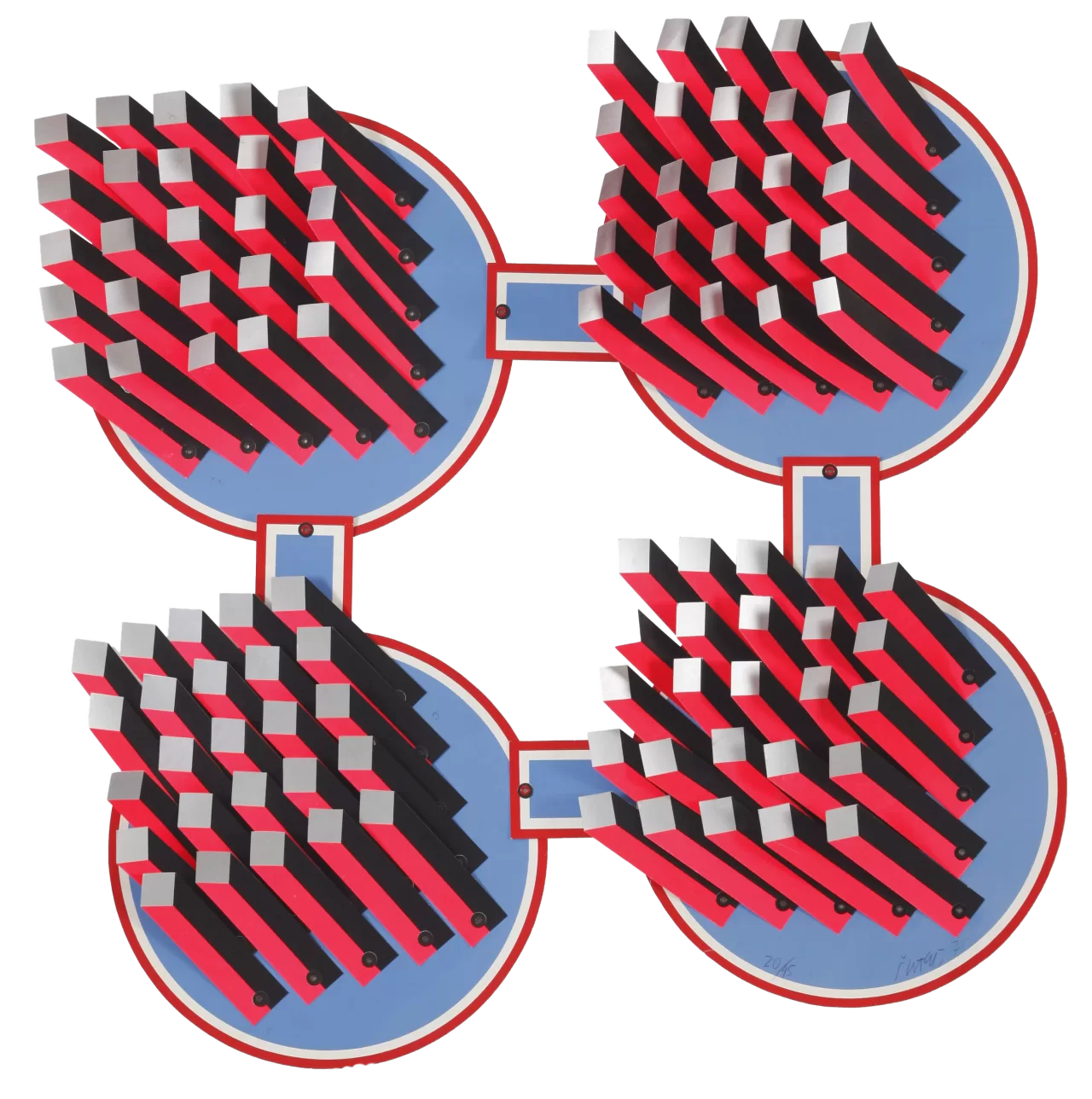

Šutej’s development in the graphic medium could be defined as a path from optical sensations to ludic mobiles, highlighting two key moments of his graphic creativity – Op art and mobile prints, also the focus of this exhibition.

After the initial black and white drawings in line with the new optical art, presented at his debut solo exhibition at the Student Centre Gallery in 1962, and their graphic transfers in aquatint and etching united in the Bombardment of the Optic Nerve series, Šutej makes a name for himself as the up-and-comer of the new visual direction – Op art. At that time the namesake series of paintings is also created, with Bombardment of the Optic Nerve II (1963) as Šutej’s first anthological piece [12] – the definition contributed to by significant exhibitions like the 2nd New Tendencies exhibition (1963) in Zagreb and Venice, followed by The Responsive Eye in New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1965. [13]

Noticing the limitations of the traditional printmaking techniques, he soon turned to serigraphy, which remained his technique of choice for the next nearly thirty years, as a new design method which could better embody his ideas and convey the experience of sculpturality. Serigraphy grew roots in Zagreb in 1957, when artist Zdenko Gradiš returned with the knowledge of the new technique, acquired in his one-year residency at the London School of Printing and Graphic Arts. The same year, its popularisation was aided by the exhibition of serigraphs by André Bloc, Edgar Pillet and Victor Vasarely at the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the publication of Picelj’s print portfolio Eight Serigraphs.

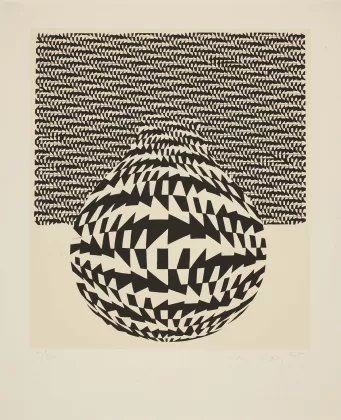

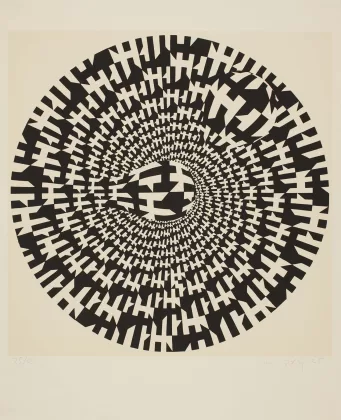

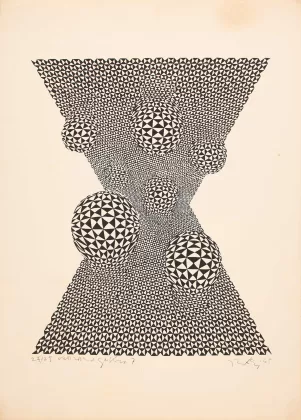

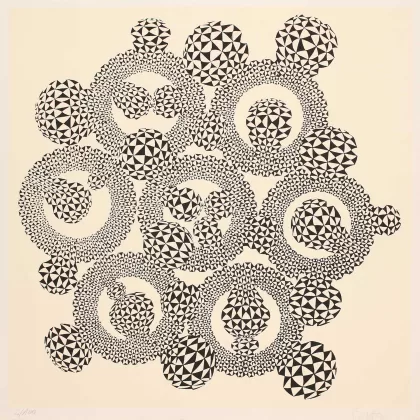

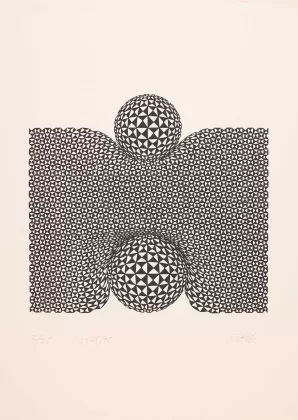

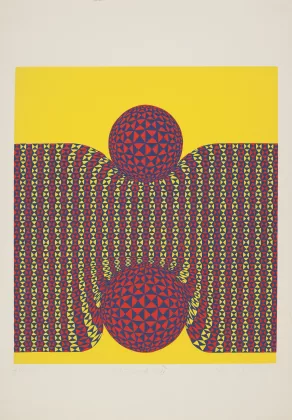

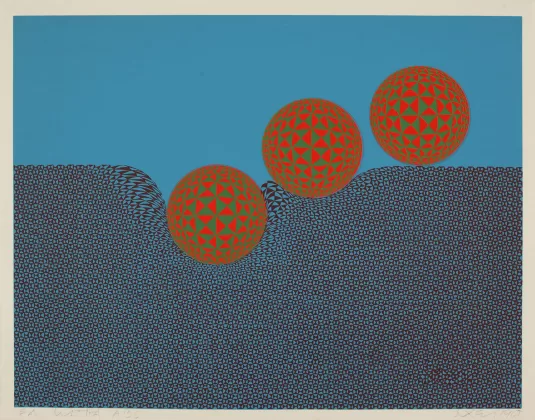

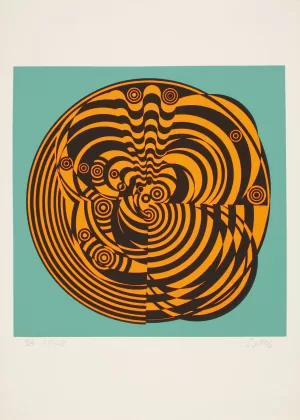

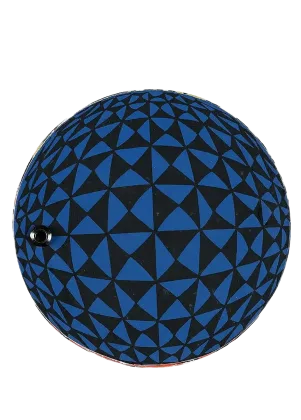

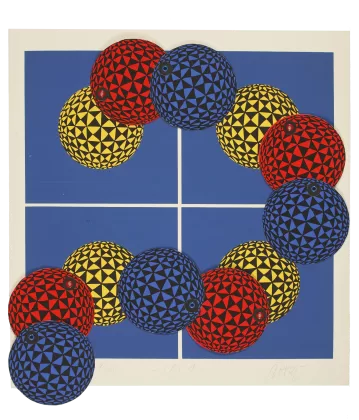

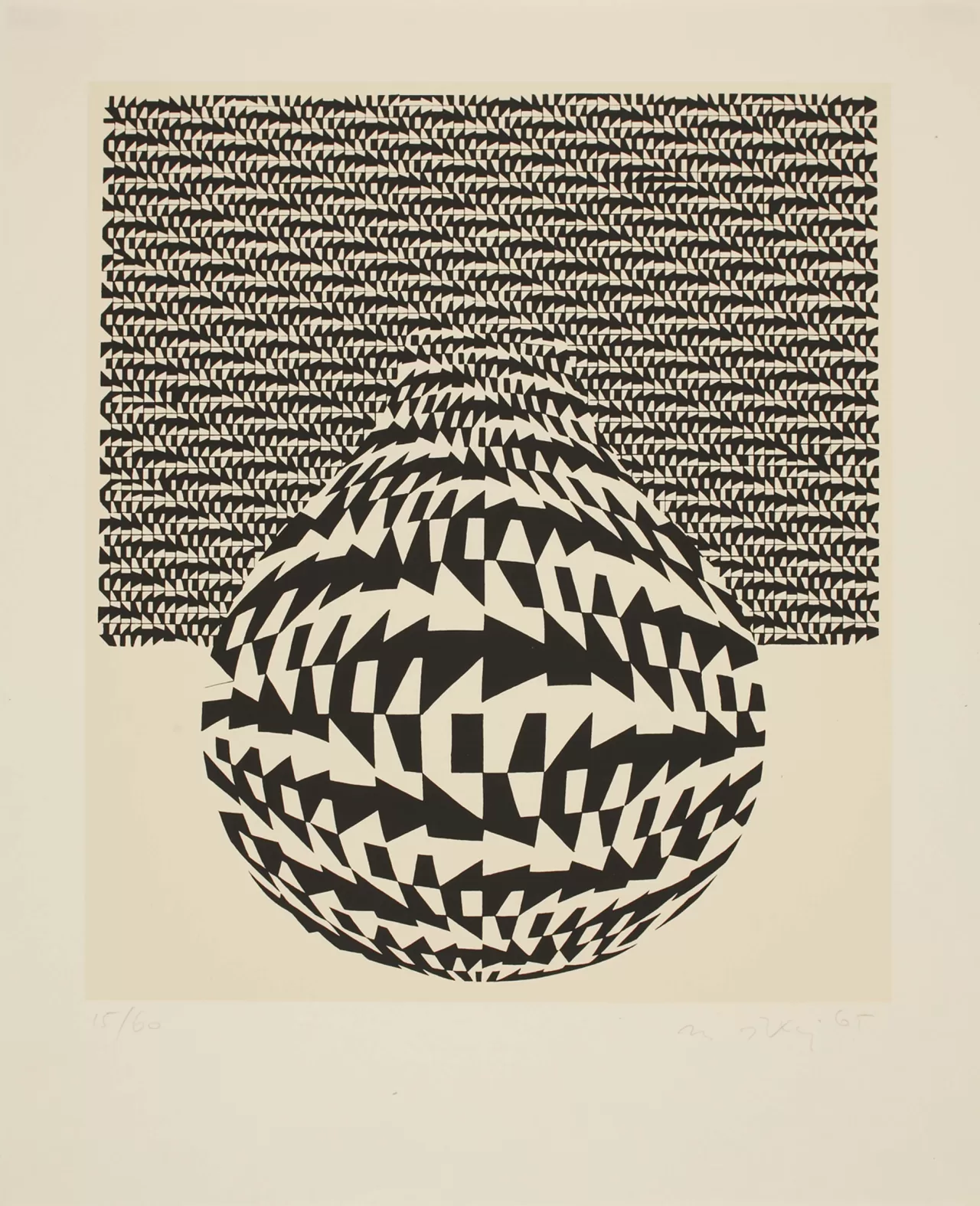

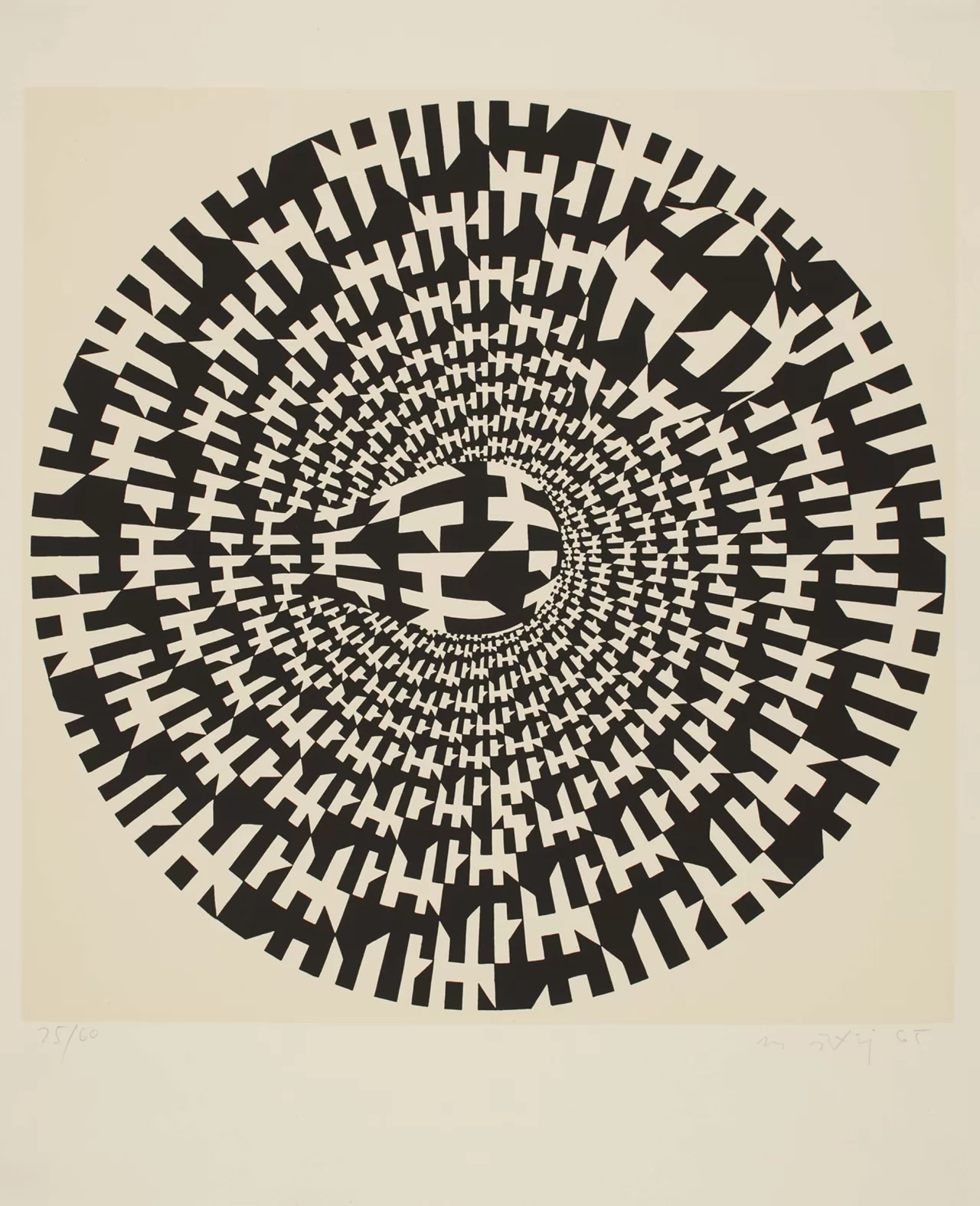

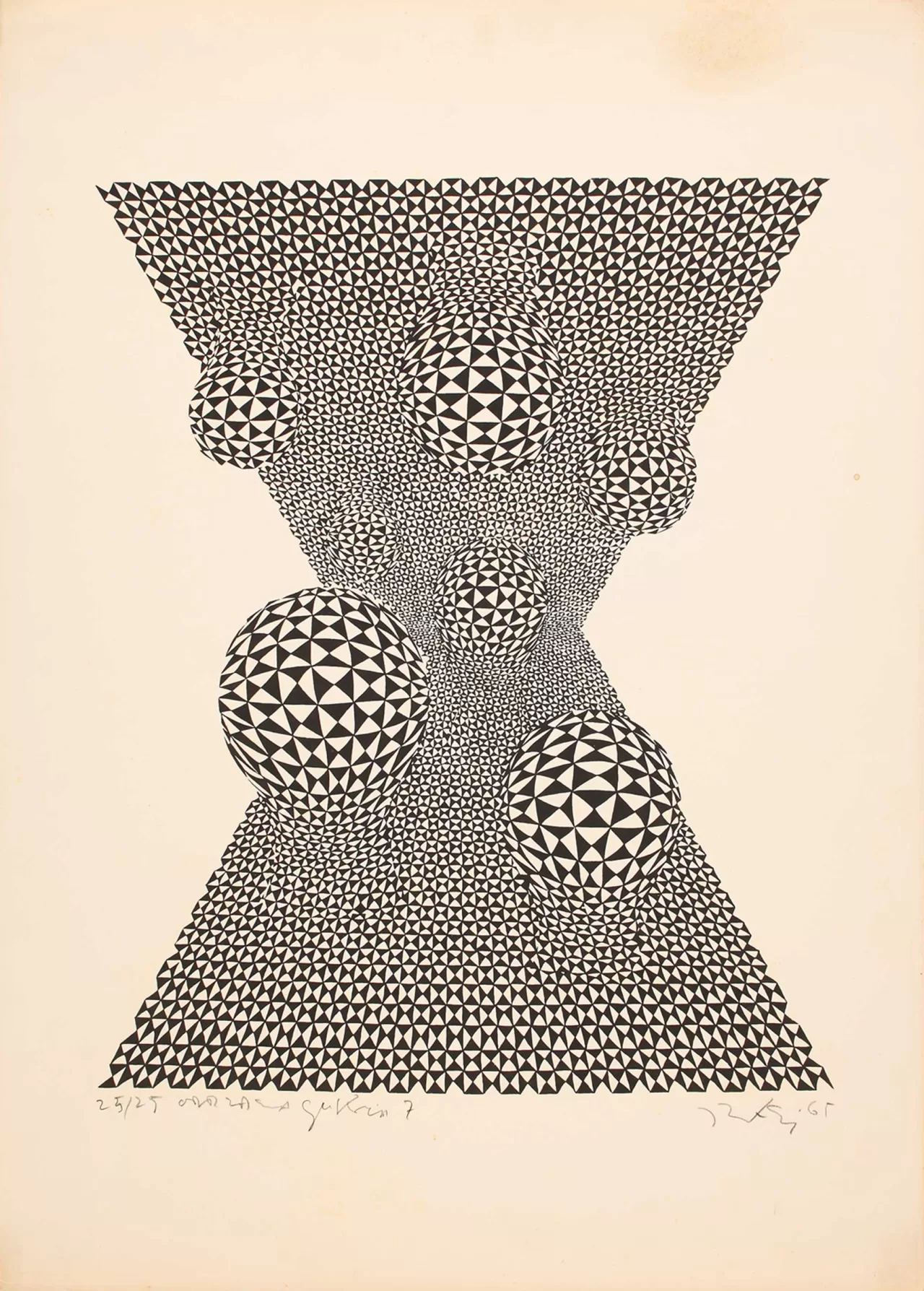

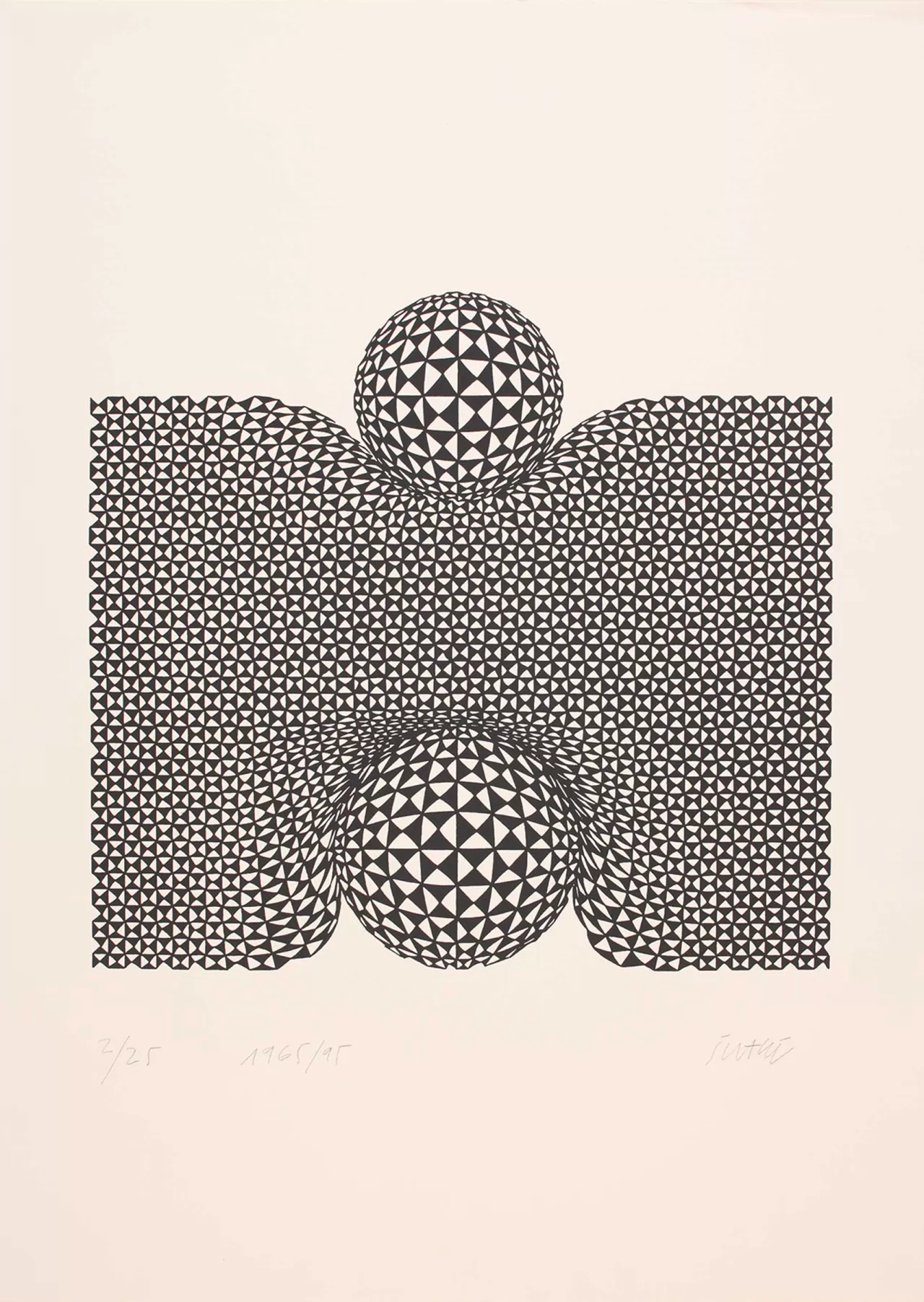

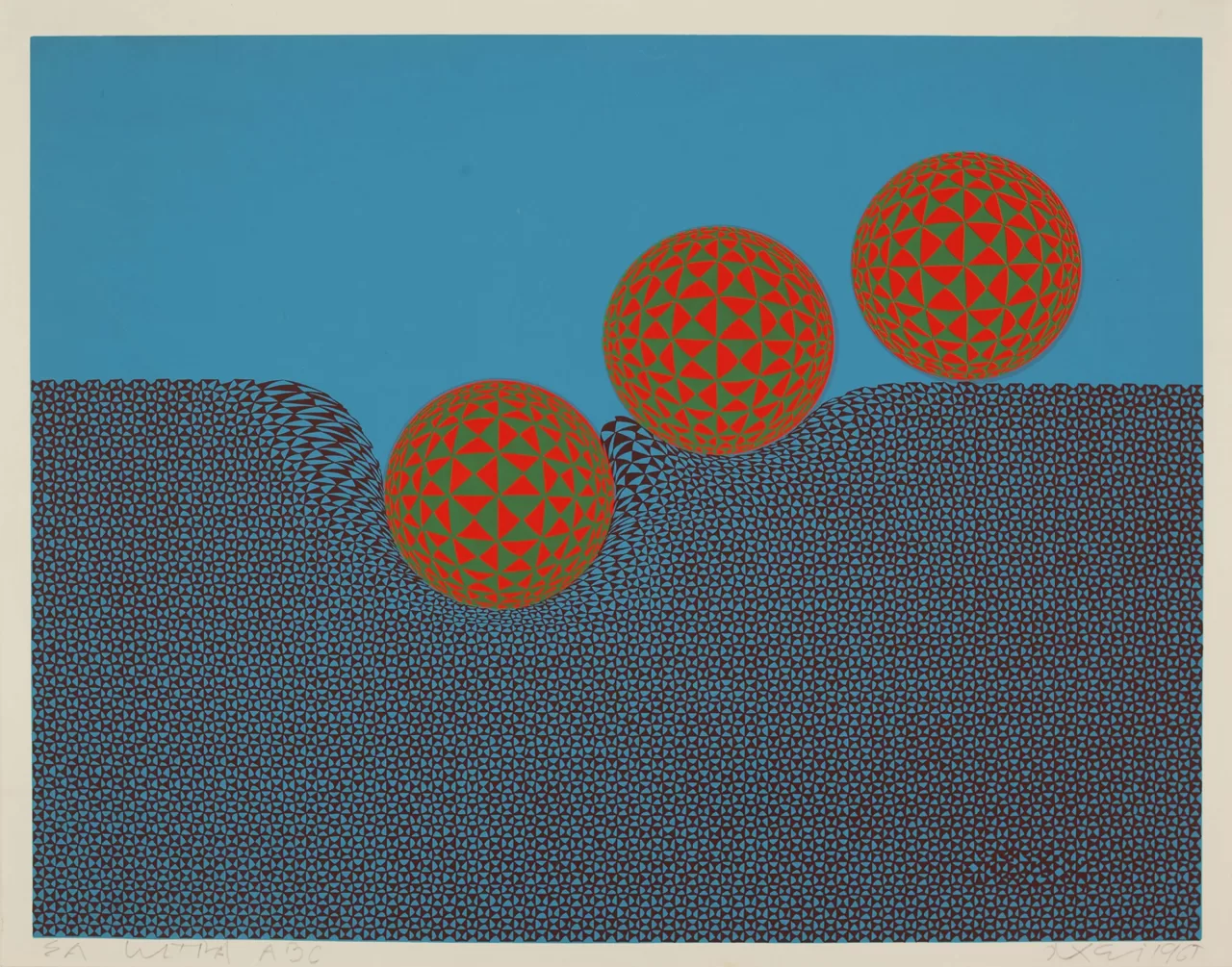

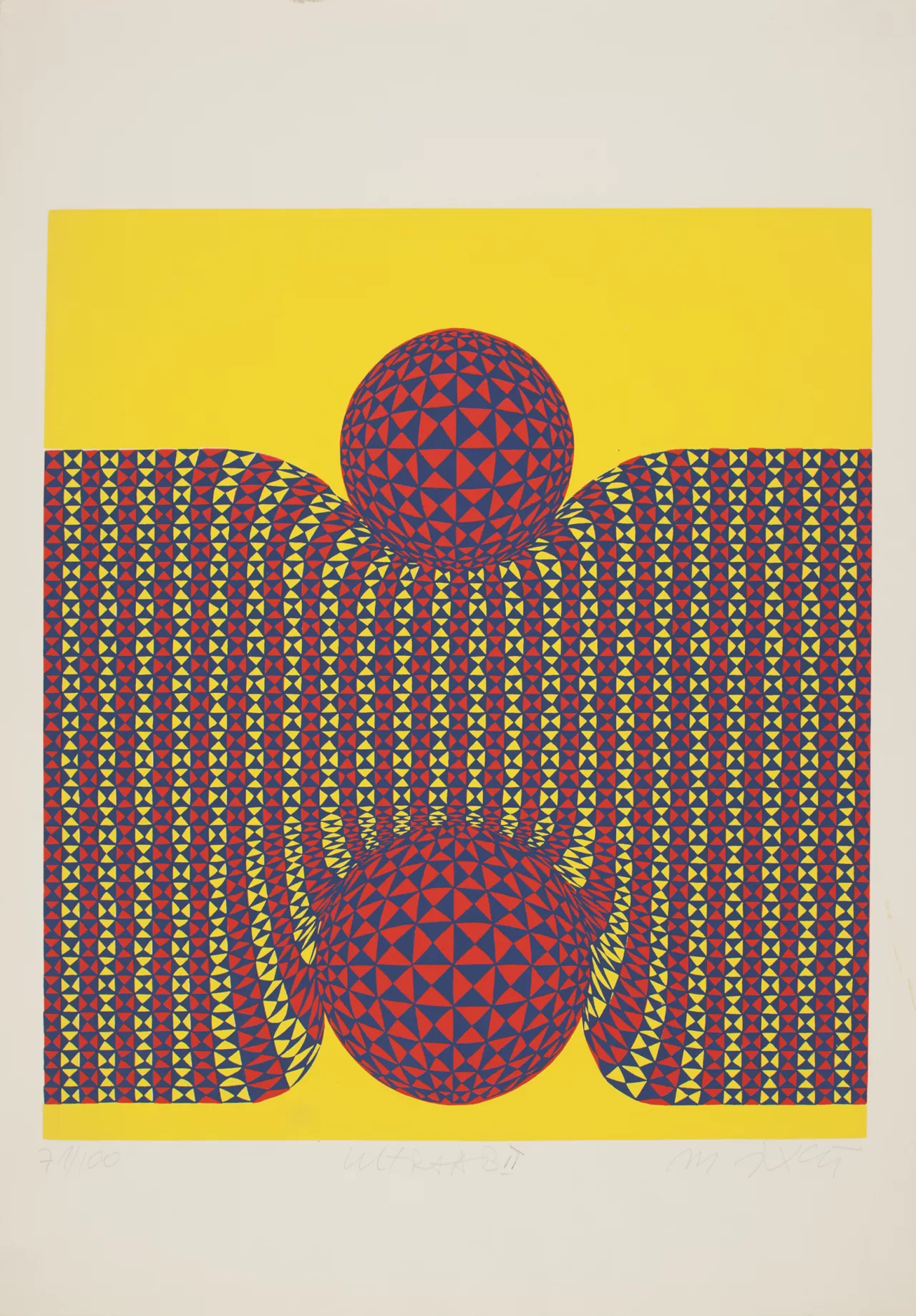

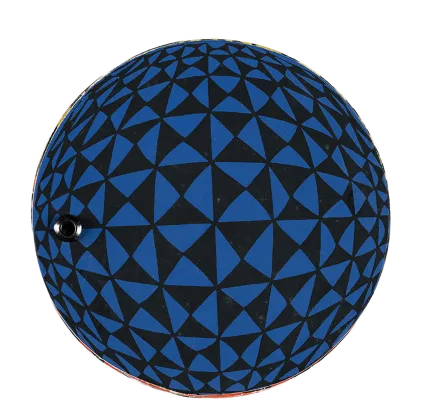

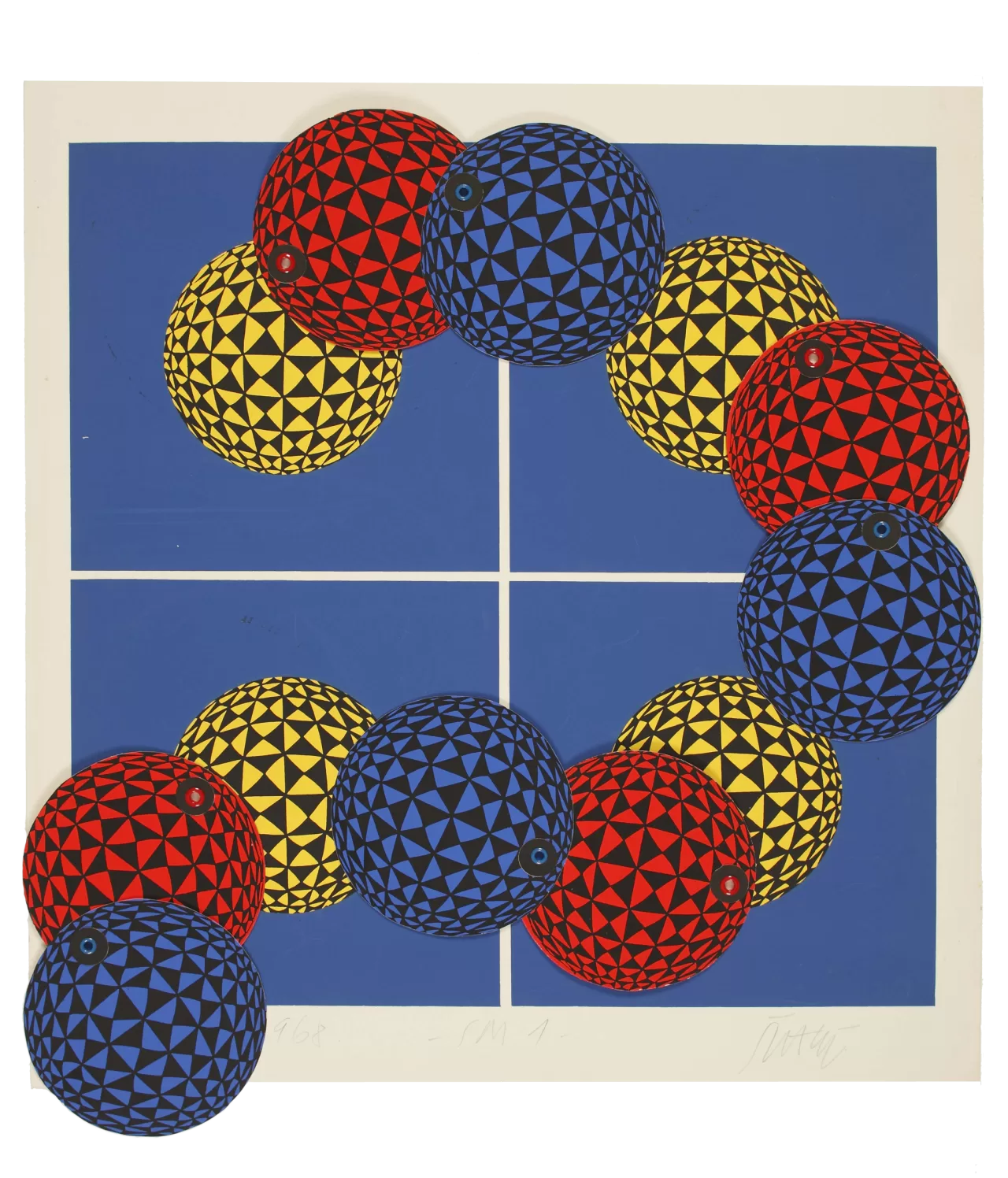

Seven years later, in 1964, Šutej made his first serigraph Bianco – nero, still designed in the wake of his earlier prints in etching and aquatint. However, as early as in 1956 his serigraphs feature a shift in technical mastery, especially in terms of chromatic possibilities and, even more importantly, a shift in the progress of Šutej’s Op art idea, which makes them particularly important for the general understanding of his artistic production. In them, Šutej uses new dynamic structures to expand the optical dimension onto the haptic one, examining the question of space and movement, which in turn become ongoing preoccupations of his work. In the black-and-white graphic sheets from the series Defined Quantity (Defined Quantity 1 and 2), Defined Density (Defined Density 7) and Ultra AB (Ultra AB), followed by the colour serigraphs Ultra AB II and Ultra ABC, a follow-up on the series Ultra AB, with the use of optical illusion he creates complex compositions whose planes seemingly embody and move spheroid shapes (circle, sphere, semi-sphere etc.). He achieves the optical illusion of the complex dilatational possibilities of the surface, i.e. whirling, growth, concaving and convexing, reduction and expansion by modulating a simple basic building element – a small square diagonally divided into trigonal binomial units within a dense geometrically structured grid. He efficiently substitutes the achromatic contrast of the building element in the Ultra AB series with bright or fluorescent, often complementary colours. This illusion of the body’s penetration into space and movement through space, highlighted in these serigraphs, would reach its peak in the Boom Boom print from 1967.

The desire to leave the surface and penetrate into space in said series was the starting point of Šutej’s breakthrough into the third dimension. The transition from the perceptive to the physical was achieved by connecting and erasing the boundaries between several different visual types and media, creating thus new hybrid creative works, such as the painting-object K 6 from 1966, the painterly-sculptural materialisation of the Defined Density 7 (1965) serigraph. Šutej achieved the height of the idea of sculpturality or ‘objectification’ with the sculptural mobiles in 1968 by introducing the ludic element – play. [14] Play as a component of the work, as Zvonko Maković describes it, adds “a measure that makes his work fully ‘open’, as Umberto Eco defined it. The piece has become an object for play, the provoker of an observer’s ludic side who, in order to perceive the piece properly, becomes a homo ludens.“ [15] With these works from the late 1960s, Šutej joined the reigning global artistic explorations which came into focus on our art scene through the first New Tendencies exhibition (1961), which focused on the transition from painting to object, [16]and continued on the objects from the early sixties, made by the Exat members Ivan Picelj, Aleksandar Srnec and particularly Vjenceslav Richter and his transformable Reliefmeter (1964).

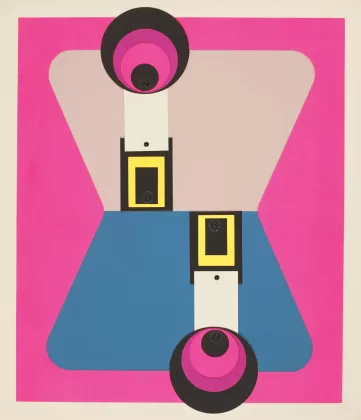

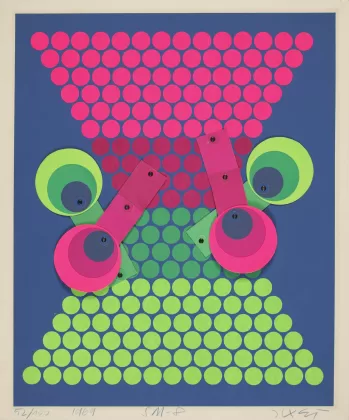

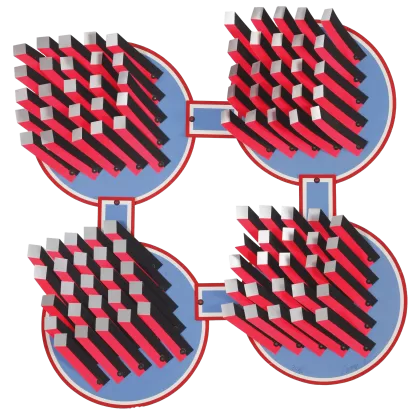

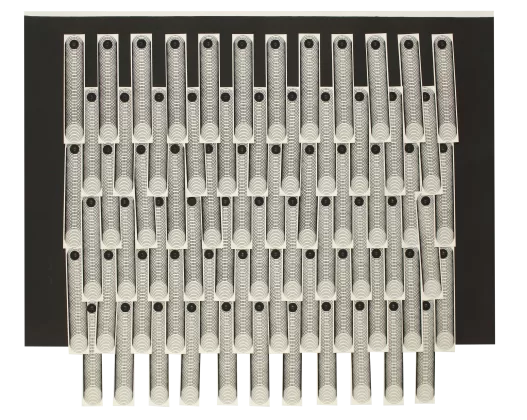

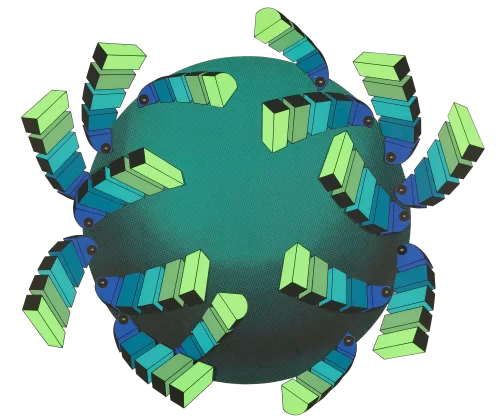

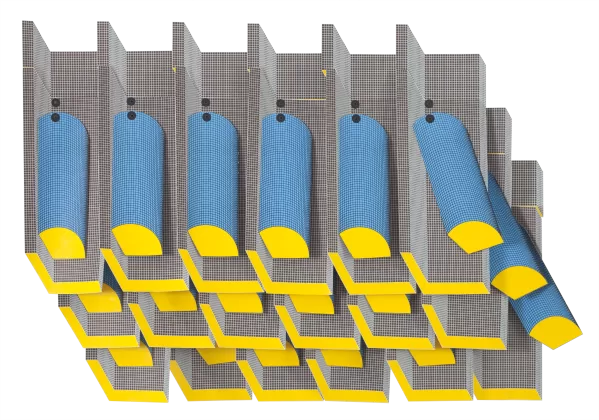

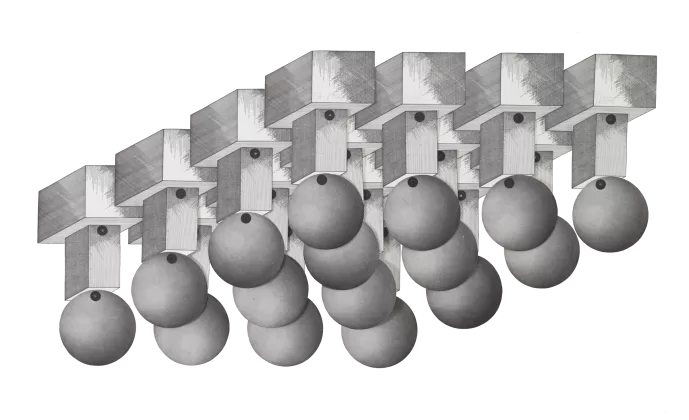

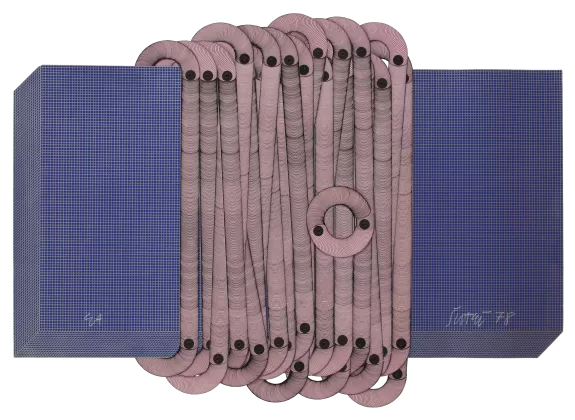

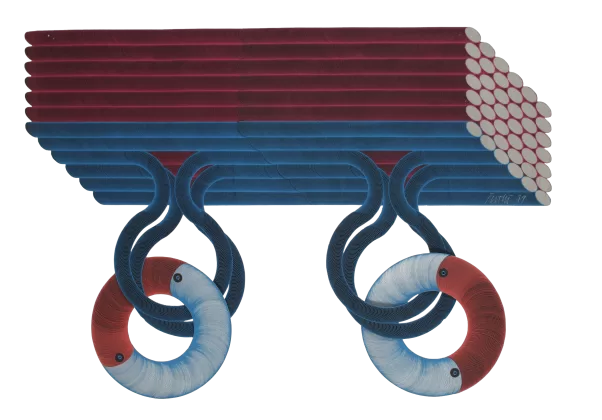

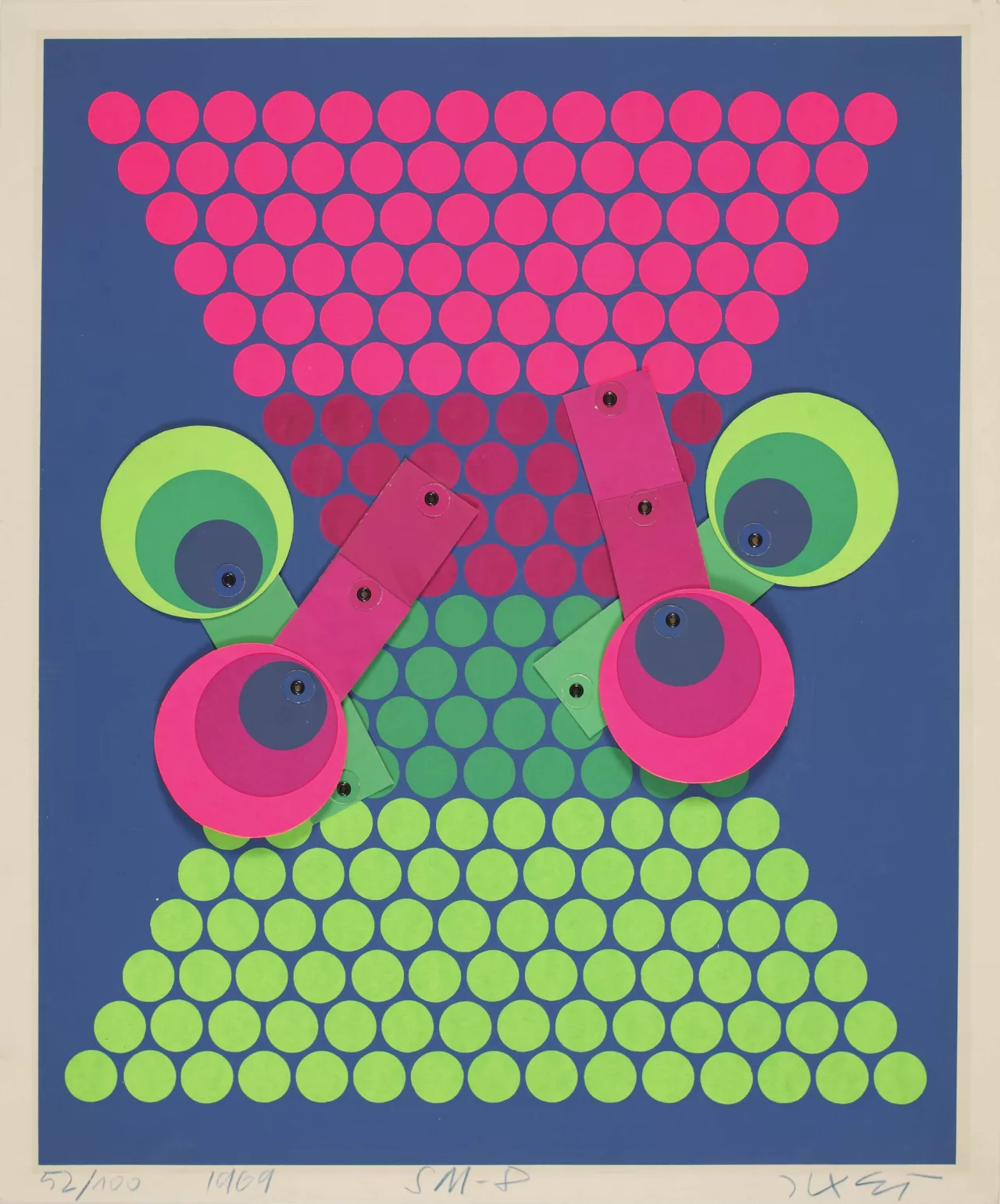

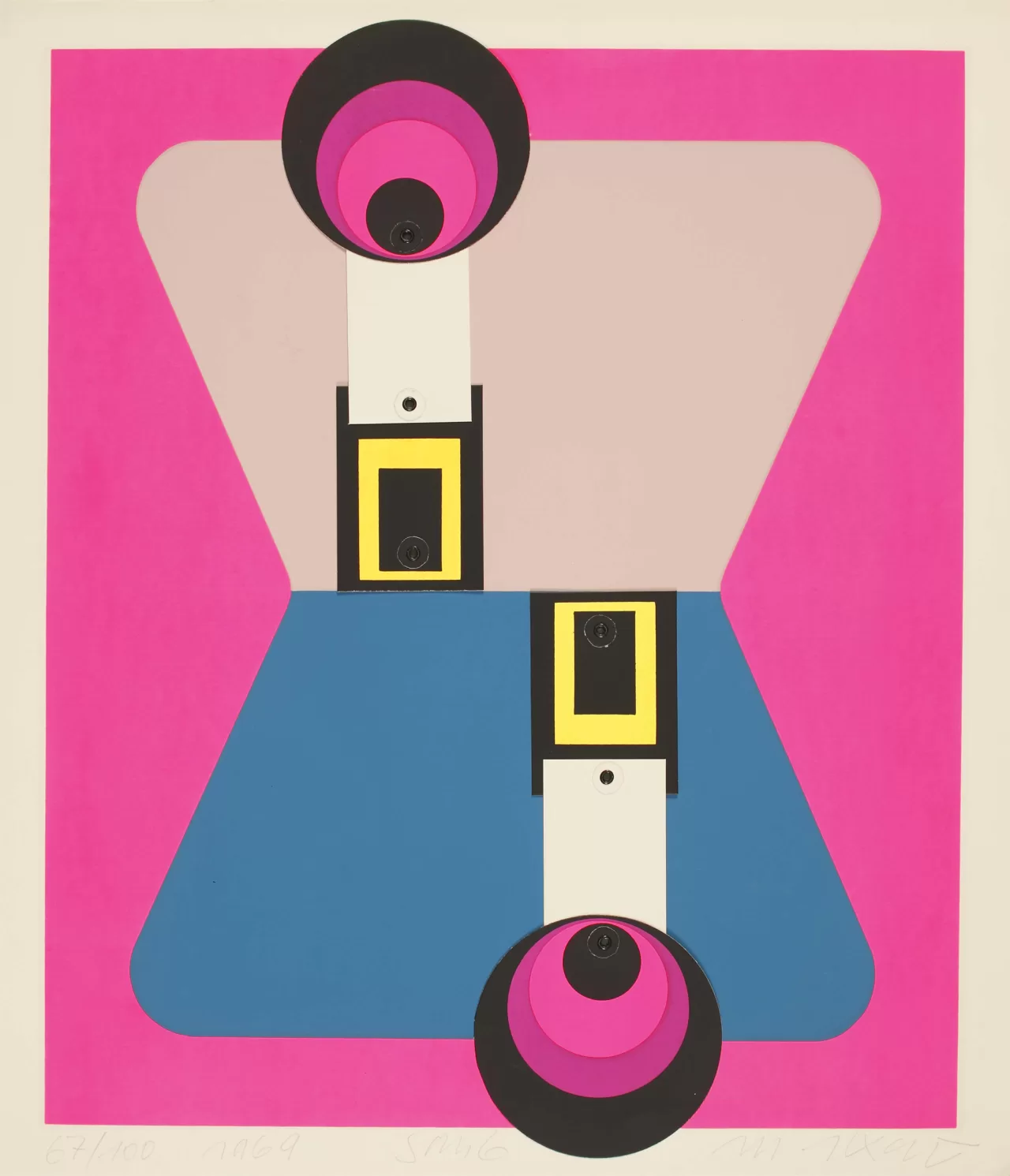

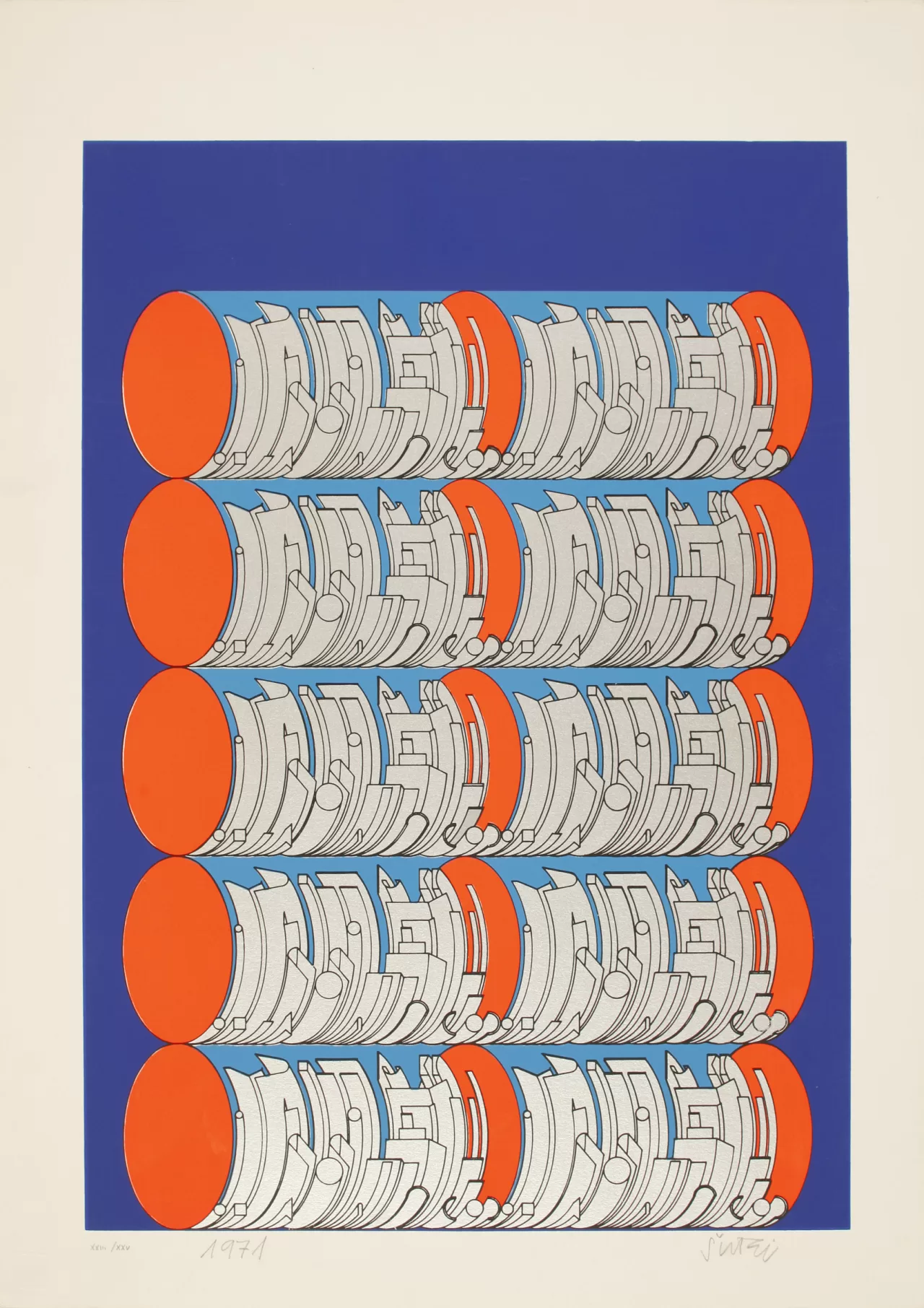

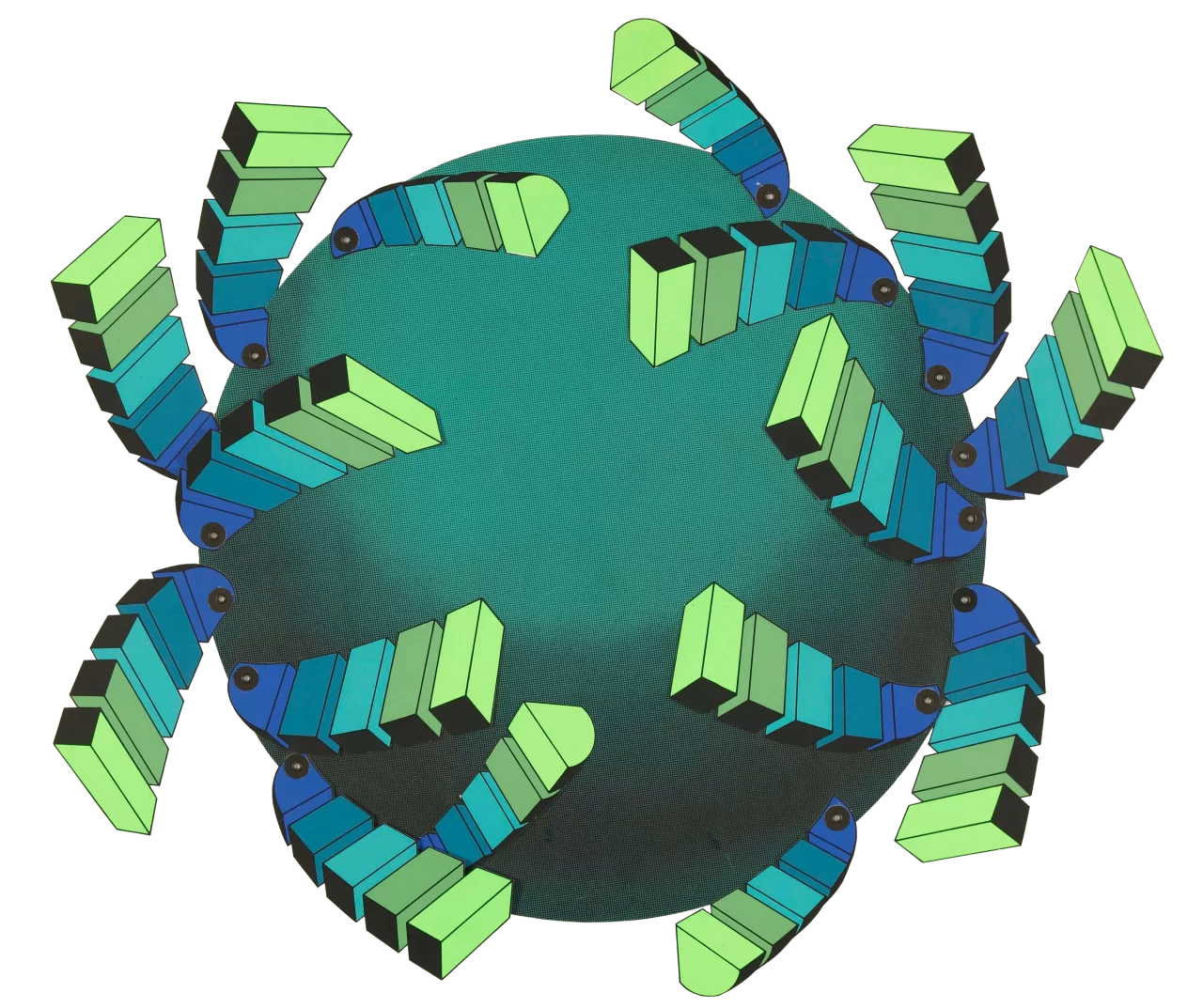

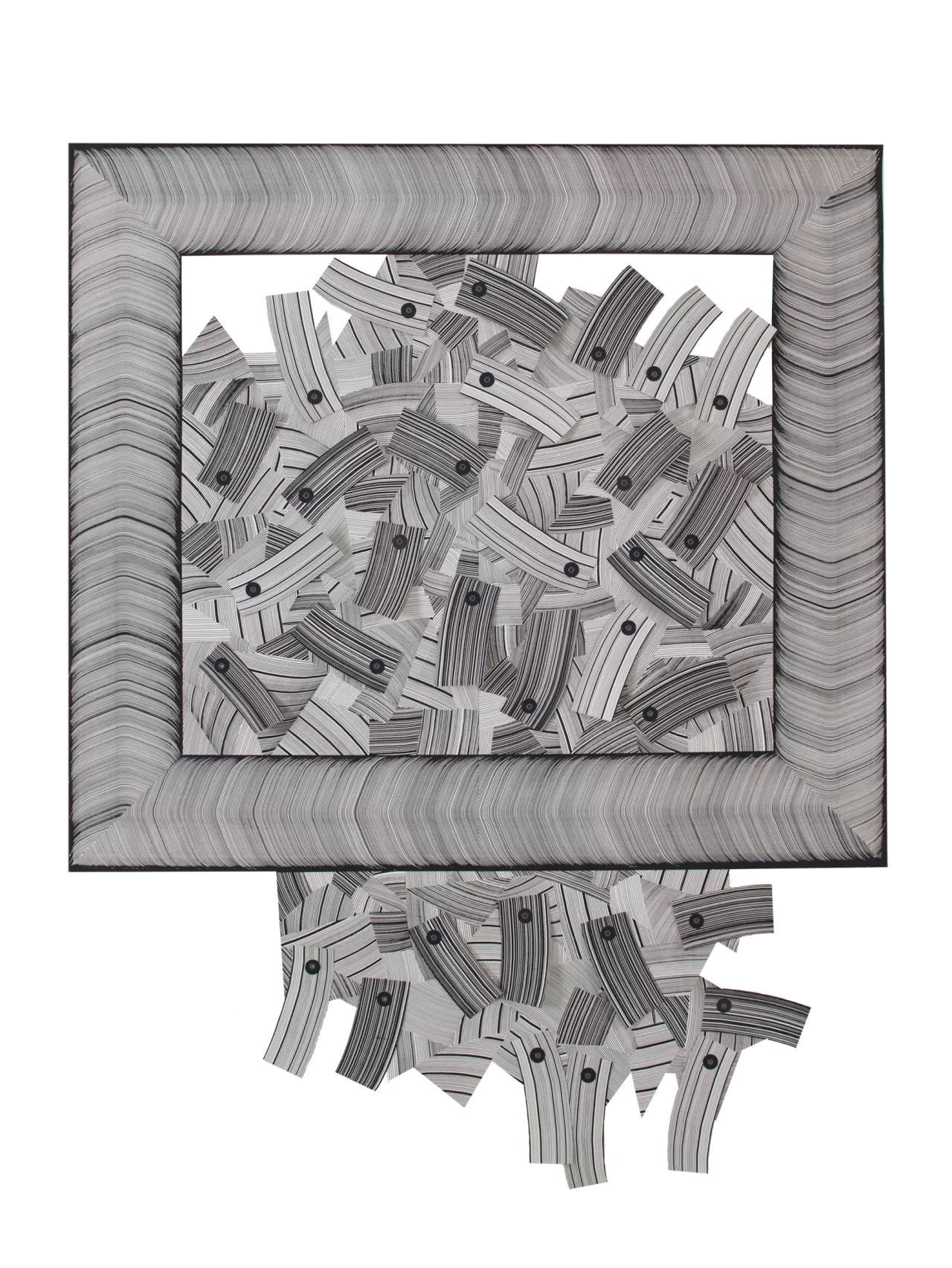

Synchronously with the mobile objects, Šutej for the first time examined the central demands of contemporary art – motion (mobility), space and openness, also in the print medium. By synthesising previous creative experience and already tested designs, leaning on, as Radovan Ivančević pointed out, the local tradition of children’s toys, [17] in 1968 he developed his first ever mobile prints Venice, SM1 and SM2. These represent the artist’s return to the graphic sheet, which he transformed with new design methods into a new hybrid species, opening it to new visual possibilities. In these initial efforts, integrating and adapting the previous powerful chromatic and illusionist effects from his serigraphs (Ultra AB II and Ultra ABC) and the mobility from his objects, Šutej gave his mobile prints a basic structure. He achieves the graphic composition’s mobility by introducing movable elements, multi-component spherical and/or rectangular elements, mutually attached by clips (Venice) and/or onto a surface (SM1 and SM2), which make it possible to create temporary and variable patterns, i.e. permutations of the compositional structure and, consequently, of the entire representation. These individual elements and multipart combinations which allow motion in all directions – the invention Ive Šimat Banov cleverly identifies as Šutej’s “ludic mechanics“ [18], are the bearers of the Ecoesque concept of an open work characterised by unfinishedness, free interpretation and the observer’s active role. [19] The composition’s changeability, i.e. a shift from the static visual original to diversely complex variations, was conditioned by the immediate contact between the observer and the work through play. Play is at the core of Šutej’s mobile prints; it invigorates the piece, it stimulates the making and the dissolving of form and develops new forms; play establishes a different compositional sequence between order and dis-order, expands the visual possibilities of a work, which subsequently depend on the observer’s imagination, and constitutes its new status and the observer’s role. Zvonko Maković explains: “The observer is motivated to activate their ludic capabilities, their imagination, and to change themselves the piece created and offered for refinement by the artist. Ideally, this leaves the work of art open thanks to countless subsequent changes.“ [20] By setting the multipart mobile arms, the instruments of play, into motion, the observer becomes an active participant, whose free involvement turns Šutej’s work into an open visual field and himself its co-creator.

With the new way of conceptualising the art form and the application of new design mechanisms of ‘ludic mechanics’, as an agent of changeability and unfinishedness and a means to incorporate the reigning definitions of contemporaneity – space, motion and openness, Šutej not only denied the auraticity of a piece and the author’s unquestionable authority, but he also contested individual postulates of the graphic discipline. Respecting the idea of the multi-original, i.e. the repetitiveness which is the essential definition of printmaking, by introducing movable elements moving inside and outside of the graphic sheet surface, and by changing its dimensions, the artist rejects the definition of the print format. Due to this deflection from customary conventions, Šutej’s mobile prints are considered graphic objects and, as such, as Slavica Marković explains, „they had a hard time passing the rigorous selection processes of the Yugoslav Print Biennial“ [21] organised by the Department of Prints and Drawings of the Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts. Although the professional terminology generally accepts Šutej’s term mobile prints, due to the elevated possibility of multiplication of the visual presentation, i.e. the representational composition mutation, they were also called multiples [22] and multi-compositional prints [23].

After exhibiting his first mobile serigraphs together with his objects at the 34th international contemporary art Biennial in Venice in 1968, as one of the three exhibitors in the pavilion of Yugoslav contemporary art, Šutej allocated increasingly more time and attention to prints in his subsequent work and the development of mobile serigraph possibilities, which, starting from 1968, became a backbone of his work for the upcoming almost twenty years. [24]

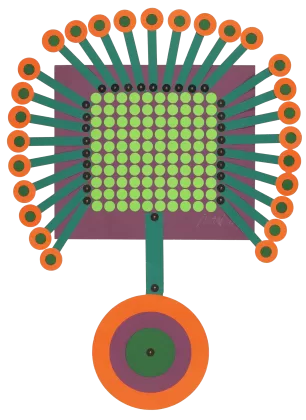

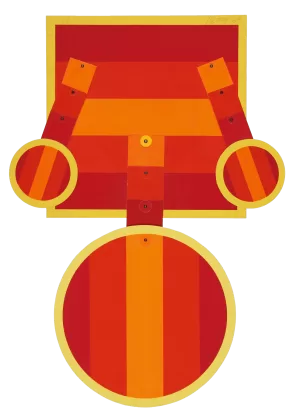

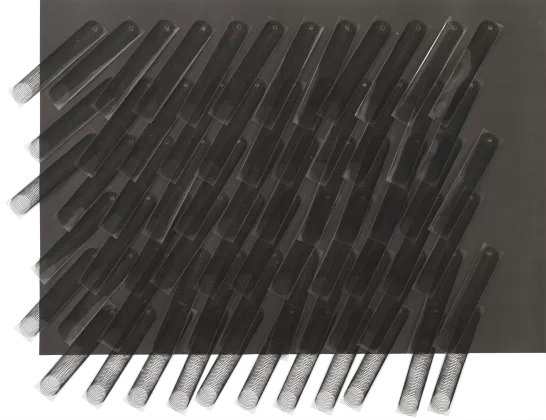

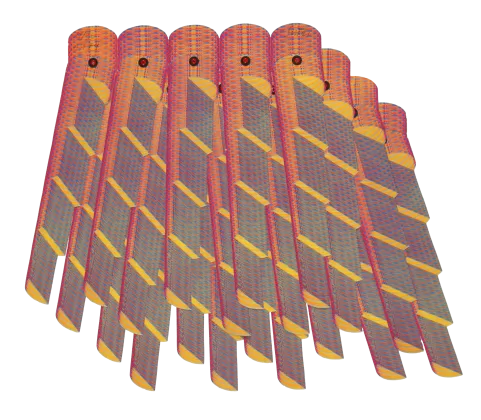

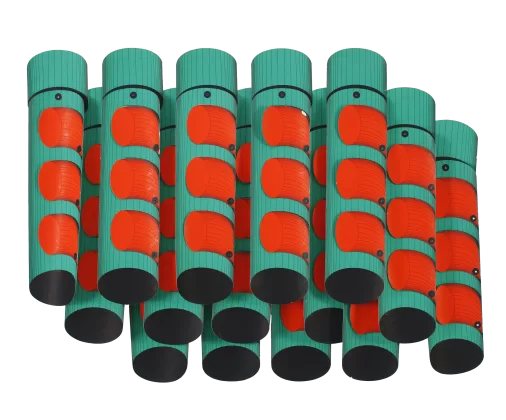

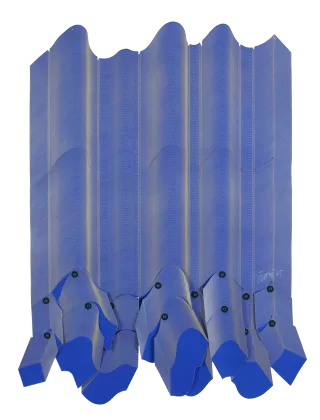

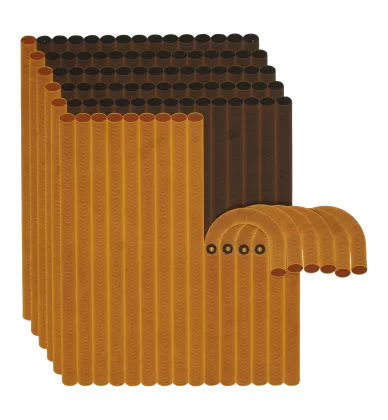

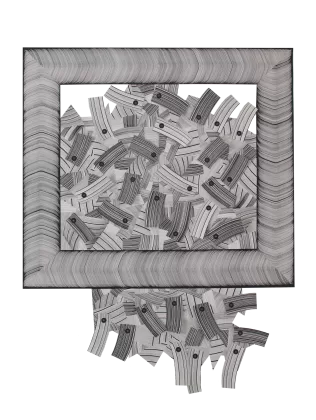

With the initial mobile serigraphs, a phenomenon typical of Šutej, began the artist’s most intense and most recognisable printmaking period (1969-1985), when he conceptualised growingly complex mobile compositions. Leaning on Slavica Marković’s typological differentiation, [25] Šutej’s mobile prints can be categorised into four groups according to compositional principles: 1. addition type, in which the mobile elements are connected in a series without a fixed background; 2. basic type, in which the mobile elements are fixed onto a solid base (background or image) and move inside and/or outside of it; 3. complex-reductive type, in which the complex mobile formations are attached to a maximally reduced background; 4. figurative type, in which the mobile elements are attached to a figurative silhouette as a background.

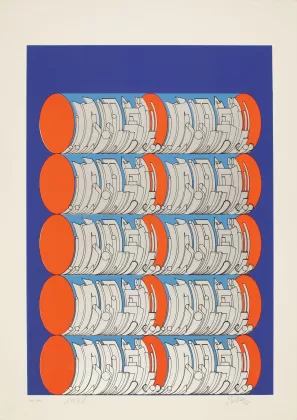

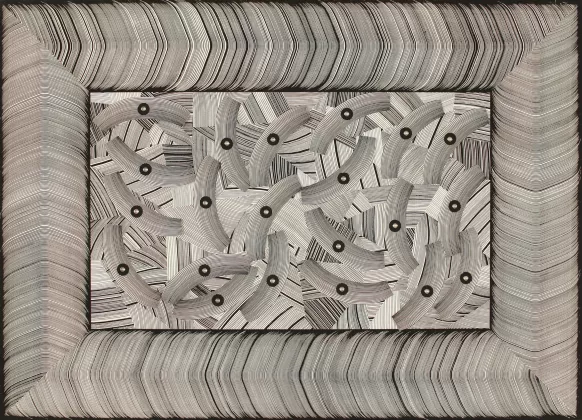

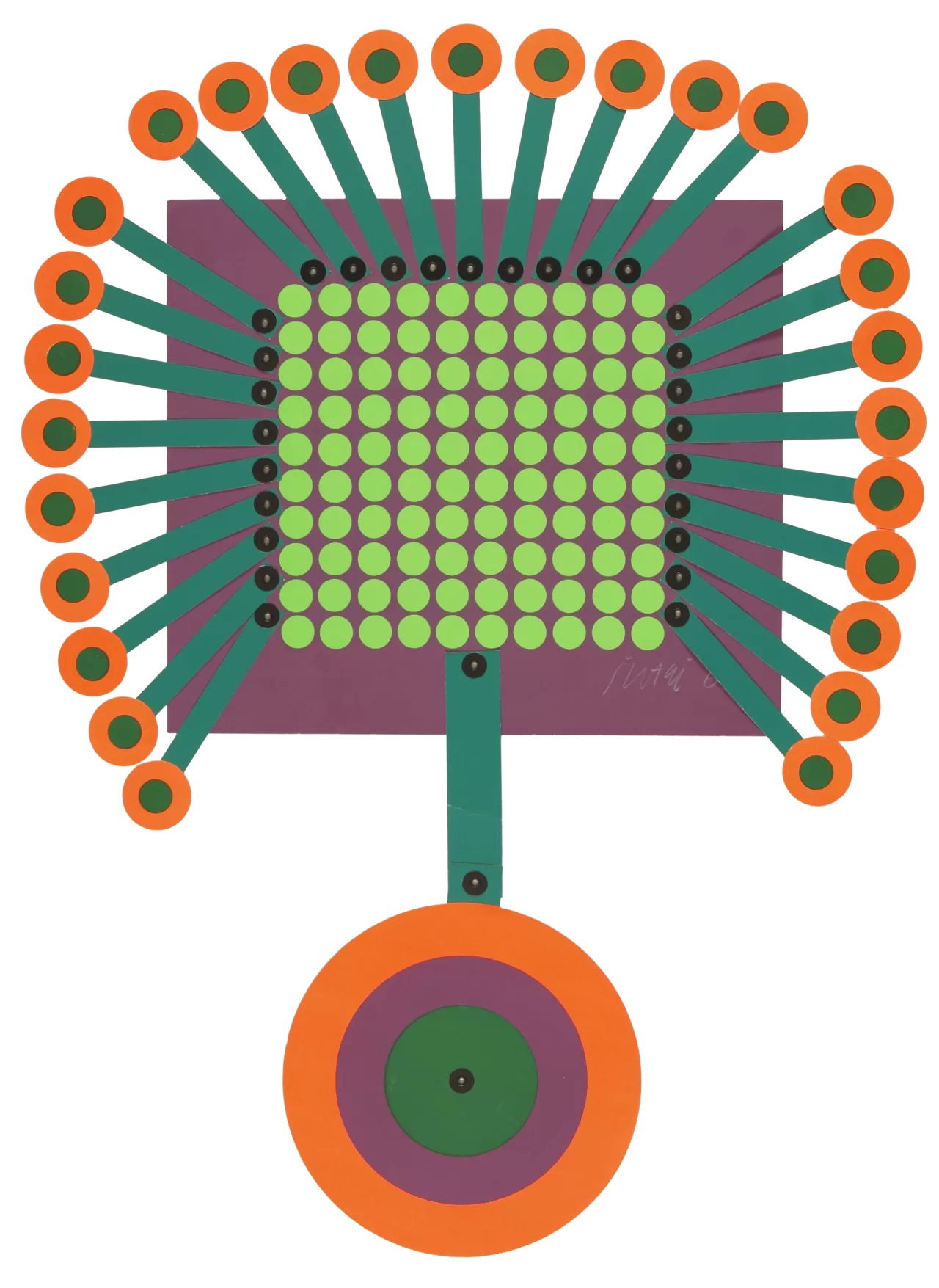

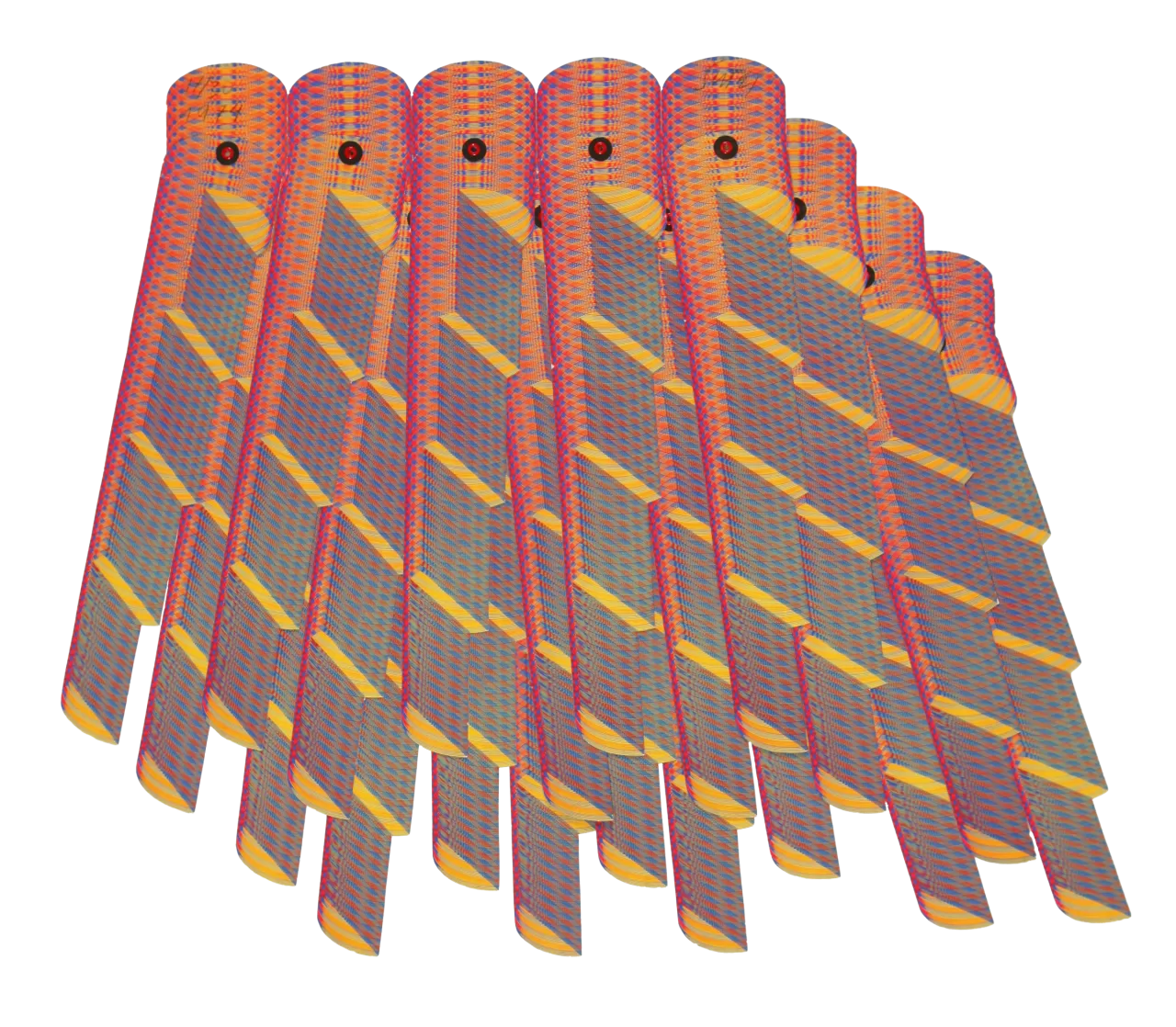

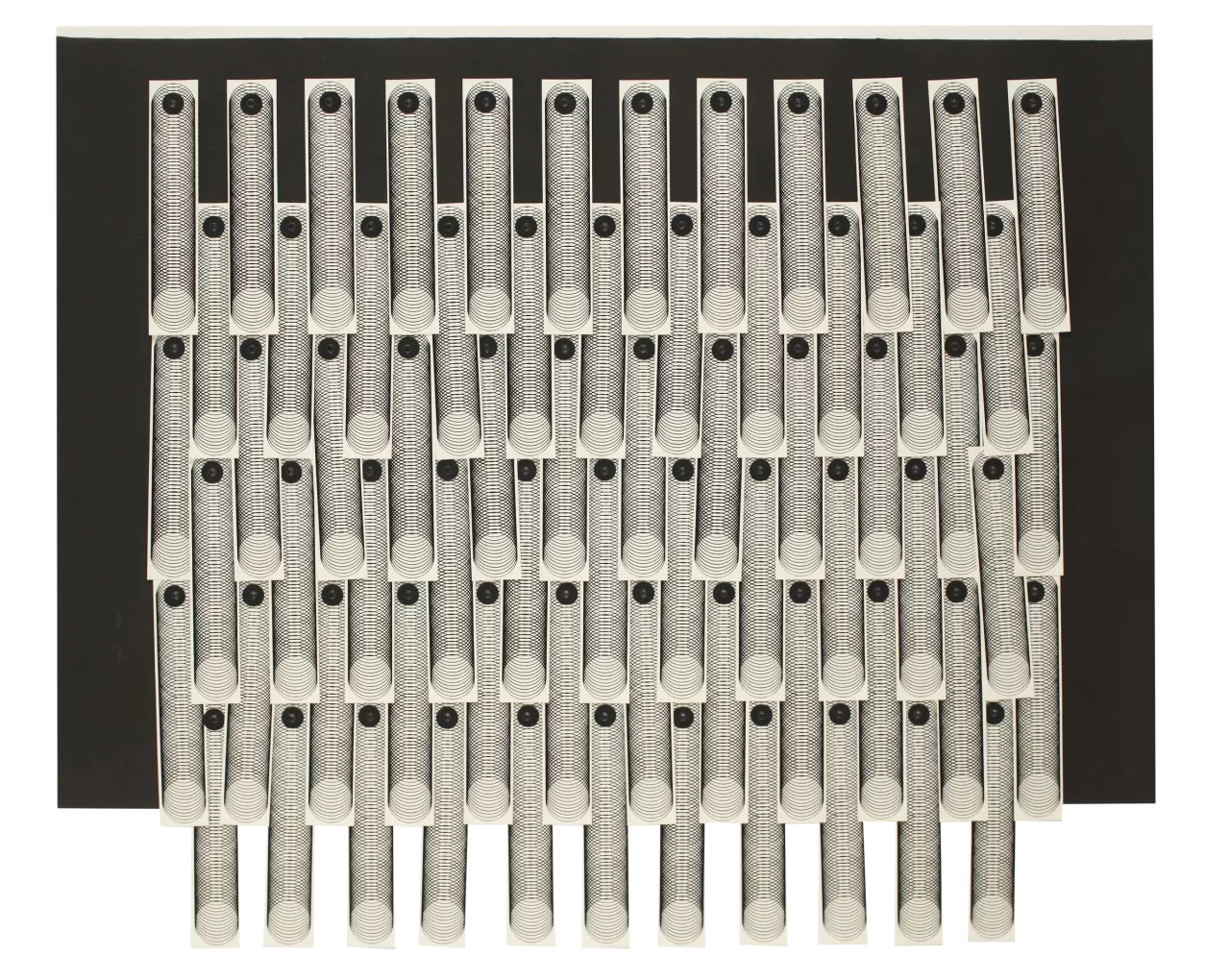

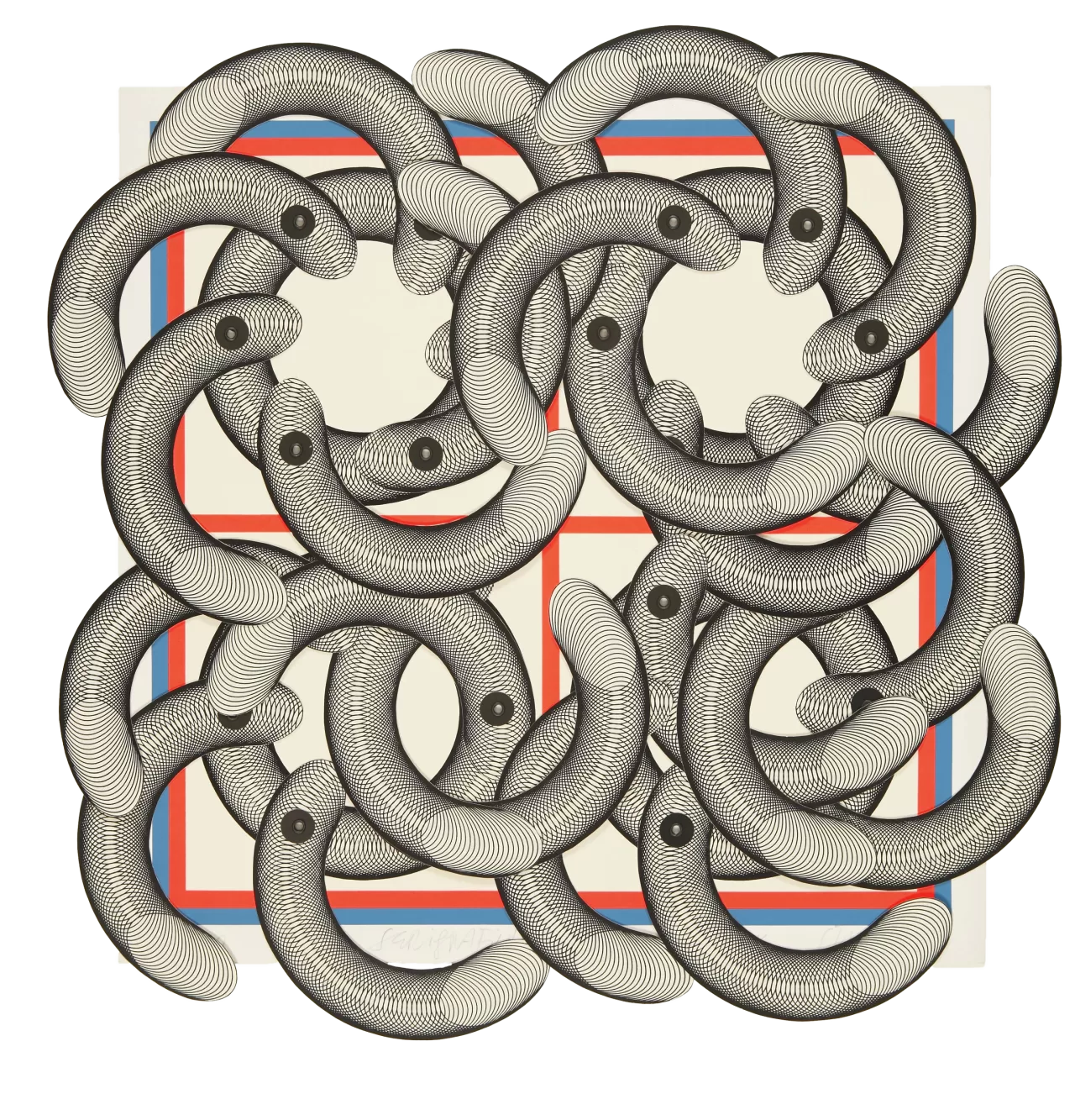

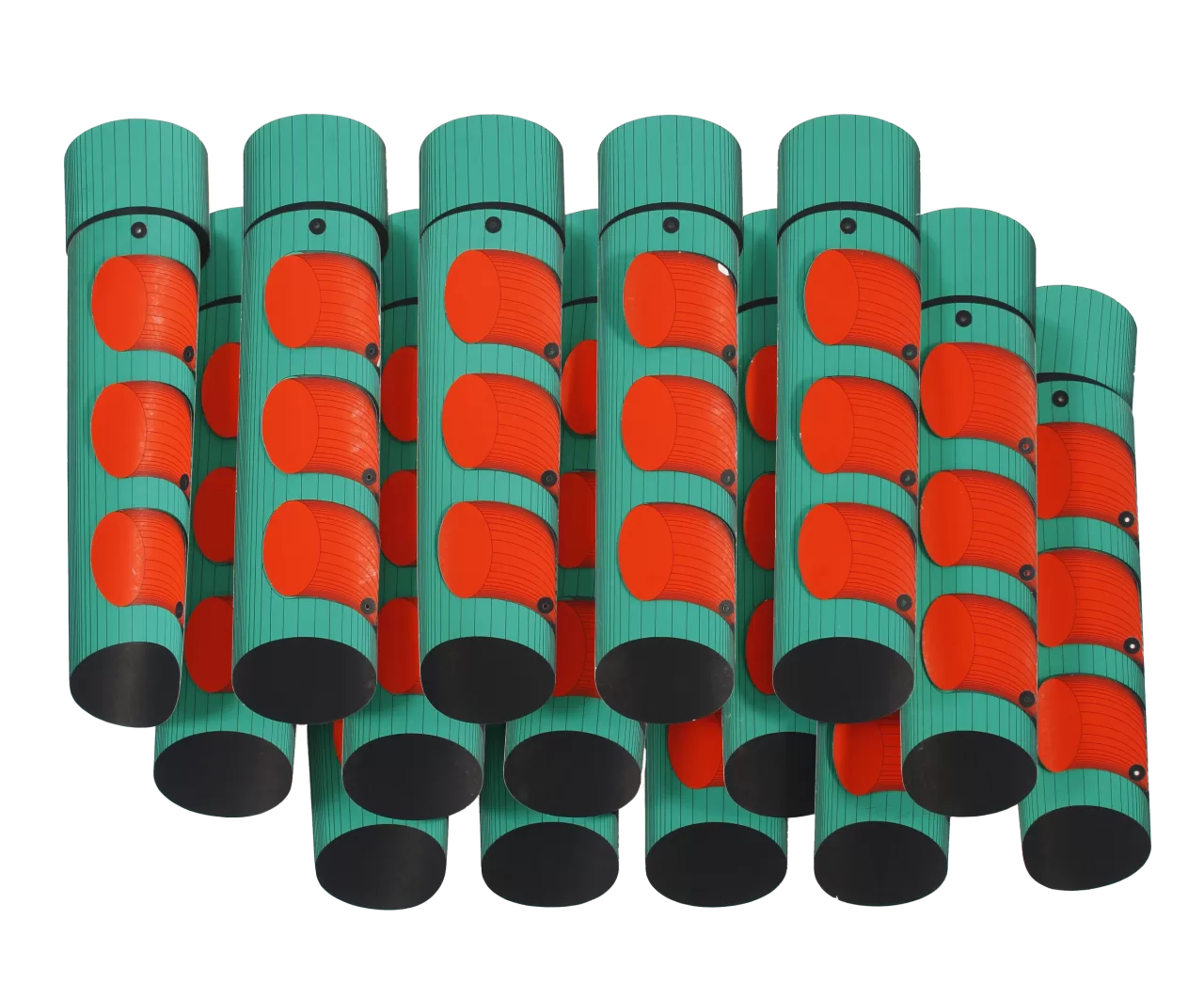

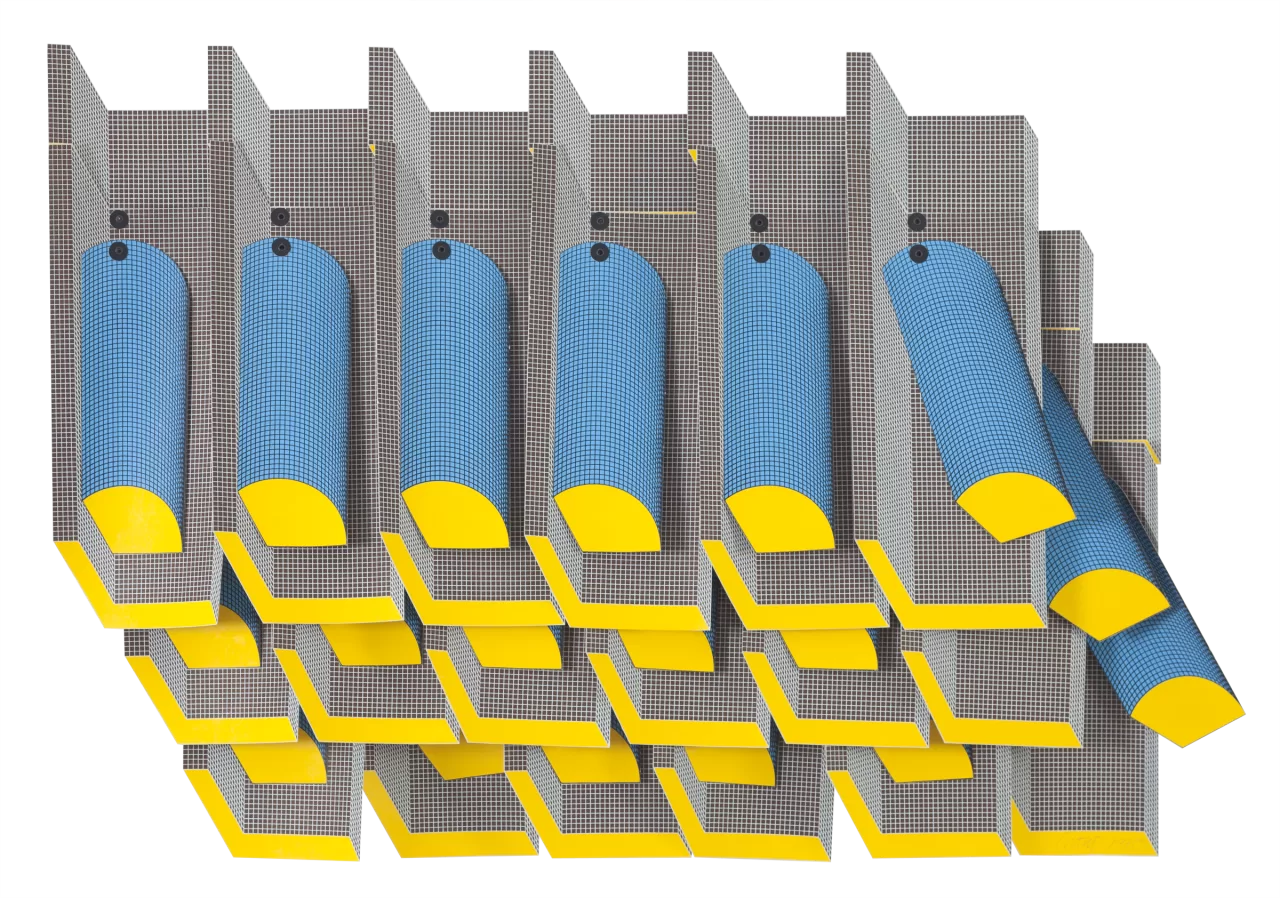

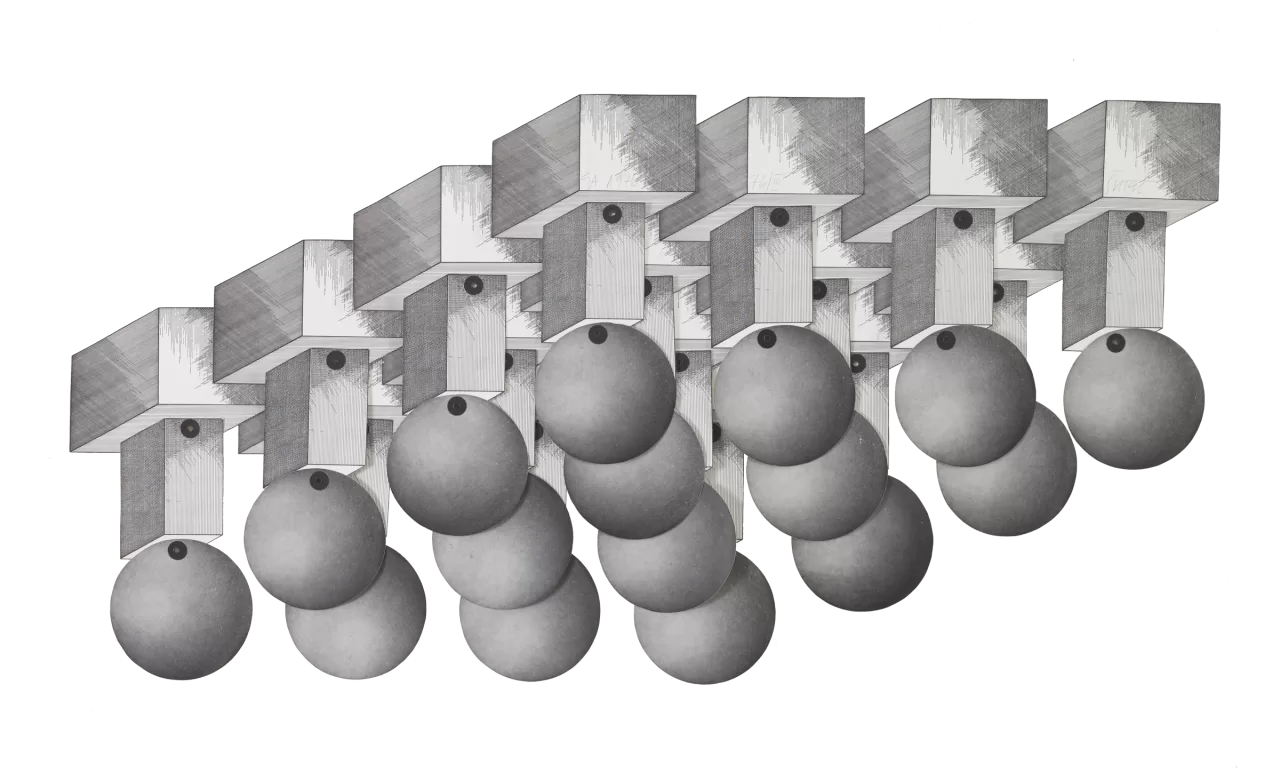

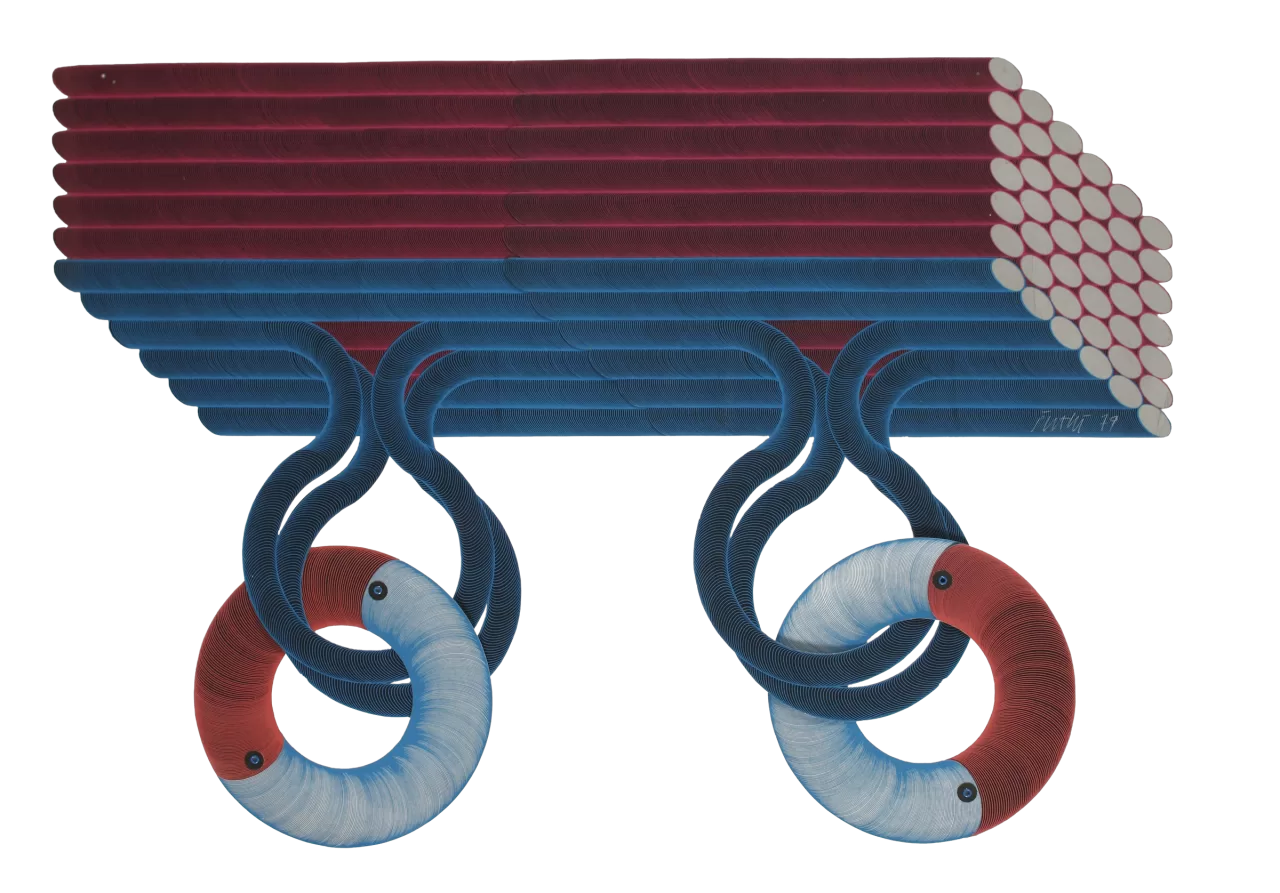

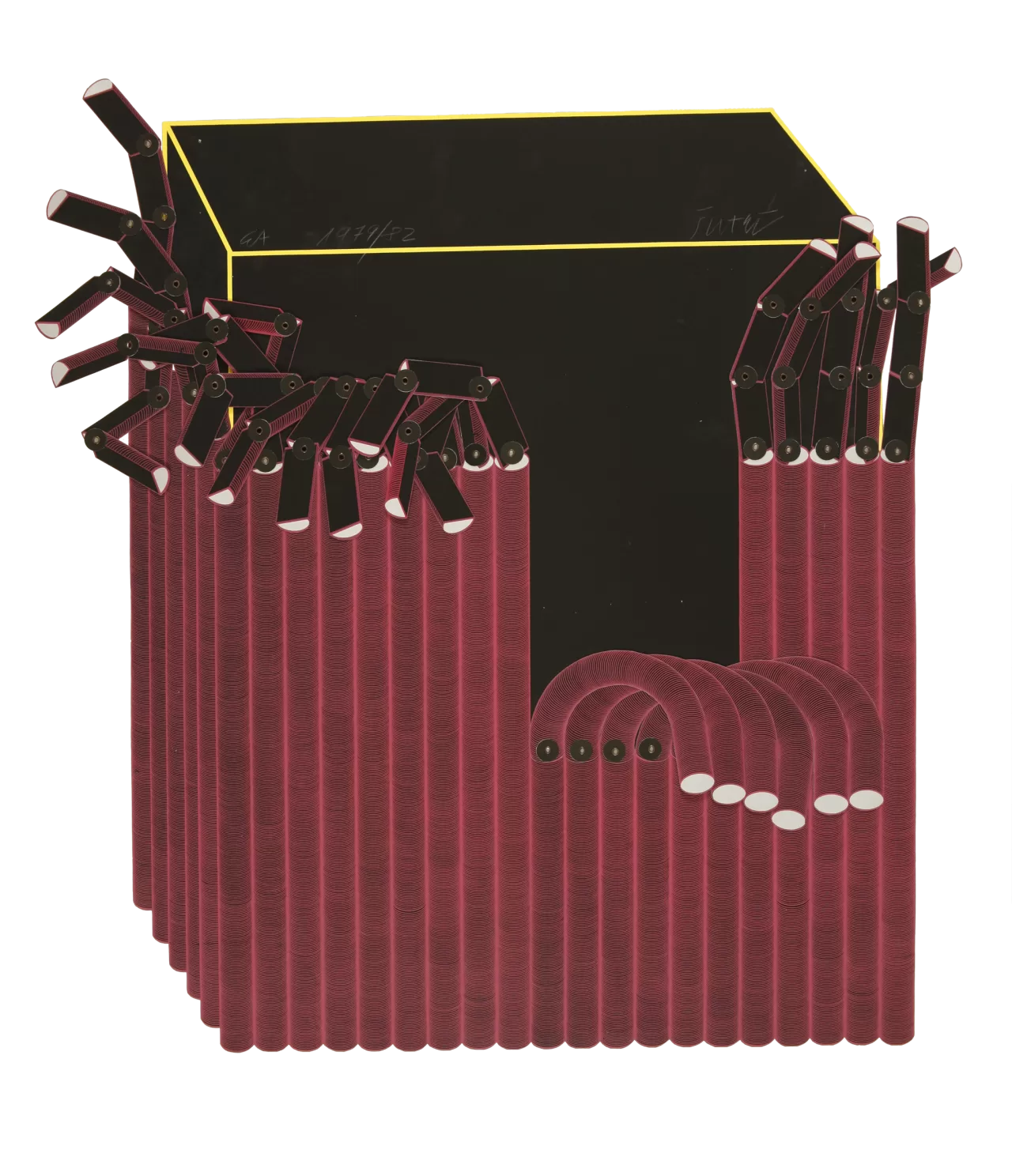

Šutej features the first two types in his first mobile prints from the late sixties. Whilst the addition type of mobile composition is an exception and appears only in the Venice print, the so-called basic type prevails as the mobile’s compositional method, ongoingly developed and variated by the artist since 1968 onwards (SM 2). In his 1969 graphic mobiles, Šutej unleashed a bright chromatic serigraphy spectrum without optical effects and satisfied himself with a somewhat smaller number of components and mobile elements (SM 6, SM 8). In this group, the exception in the number of mobile elements is the print SM 3 with several more moving arms and joints. In the early seventies, Šutej upgraded the concept and executed increasingly sophisticated mobile compositions of the basic tyle, in which motion is more complex and the number and dimensions of the movable elements grow. He also reintroduced optical effects to achieve the illusion of depth and fulness of the body (SM 9, Green Ball, Purple Ball), which is evident when comparing the earlier SM 1 print and the print Serigraph with Four Circles, where illusion is achieved by intertwining dense spiral-like lines with a possible moiré effect.

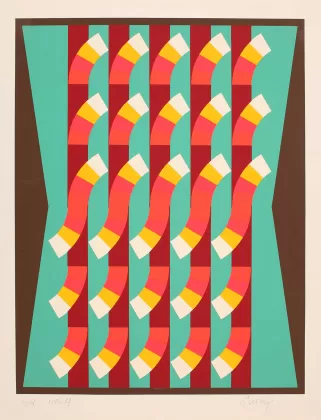

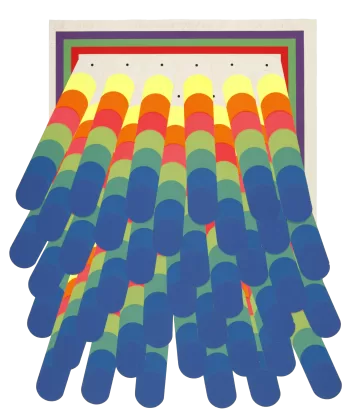

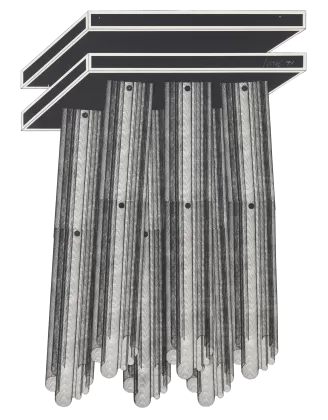

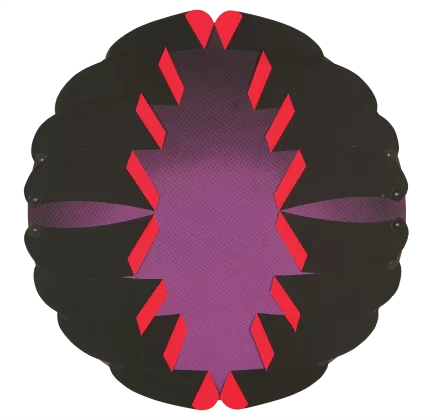

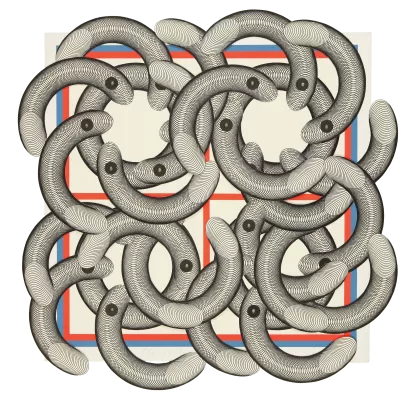

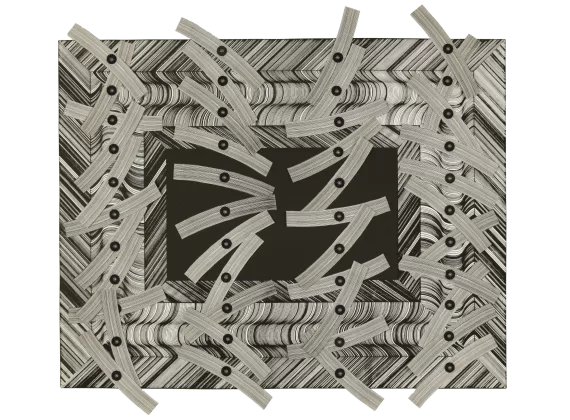

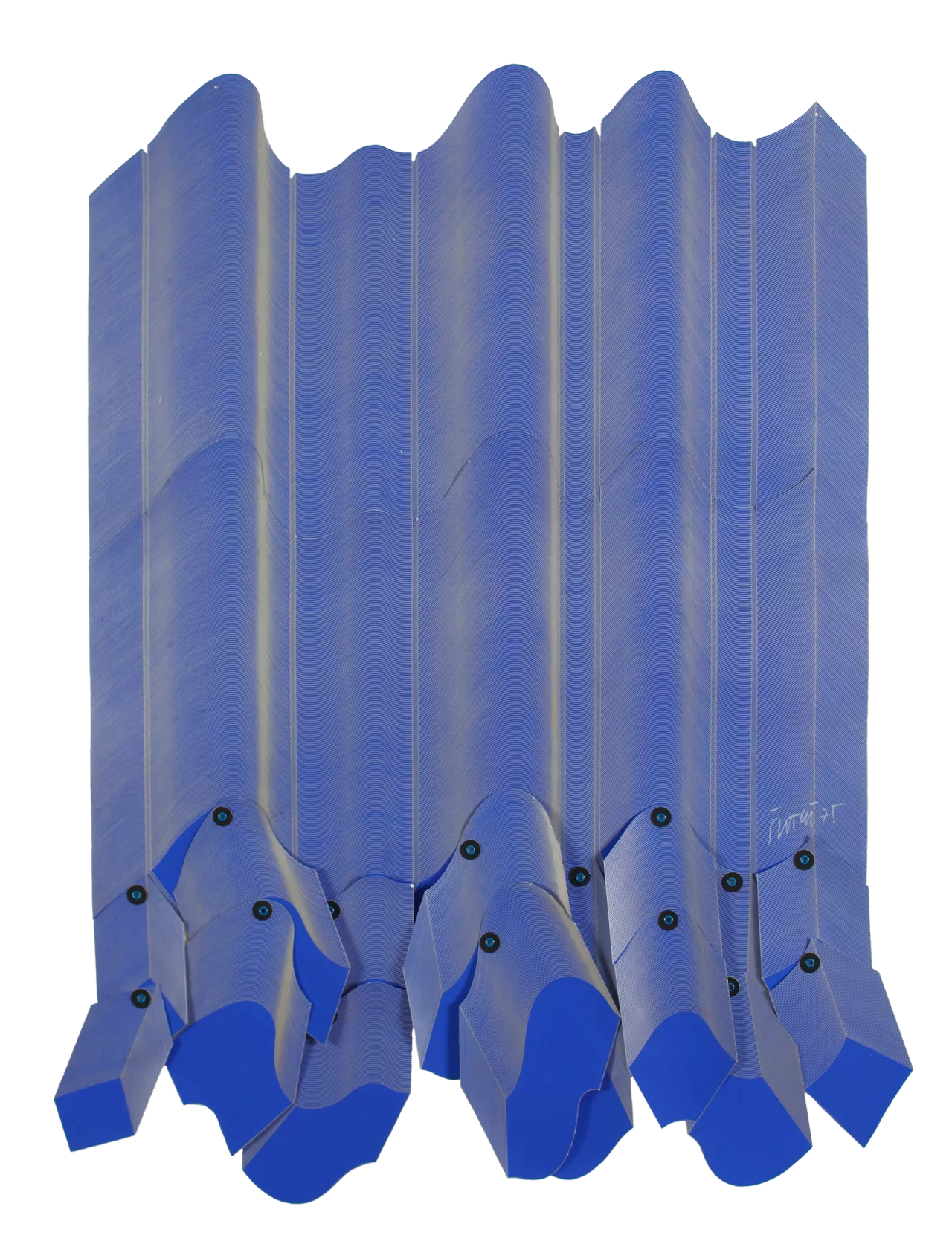

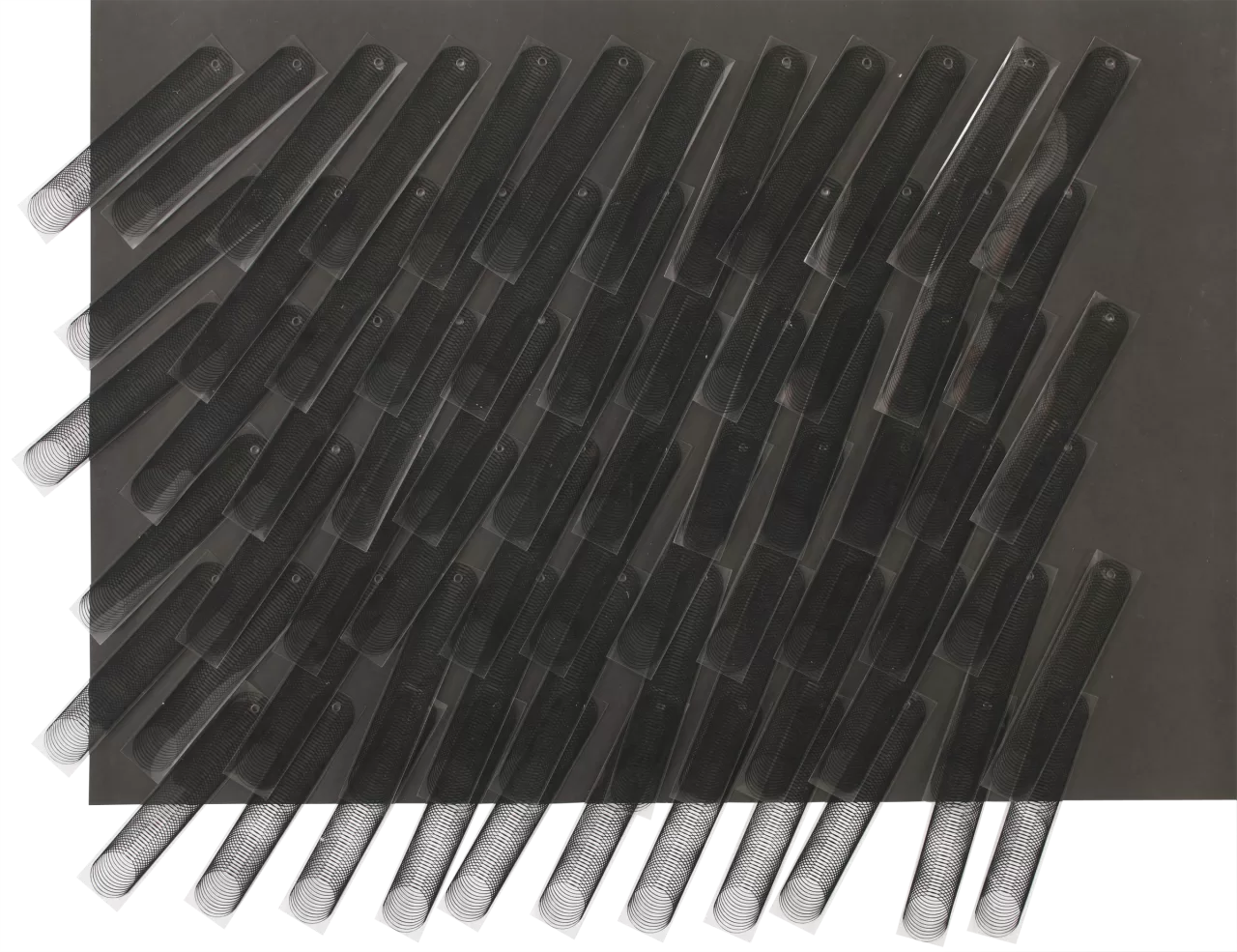

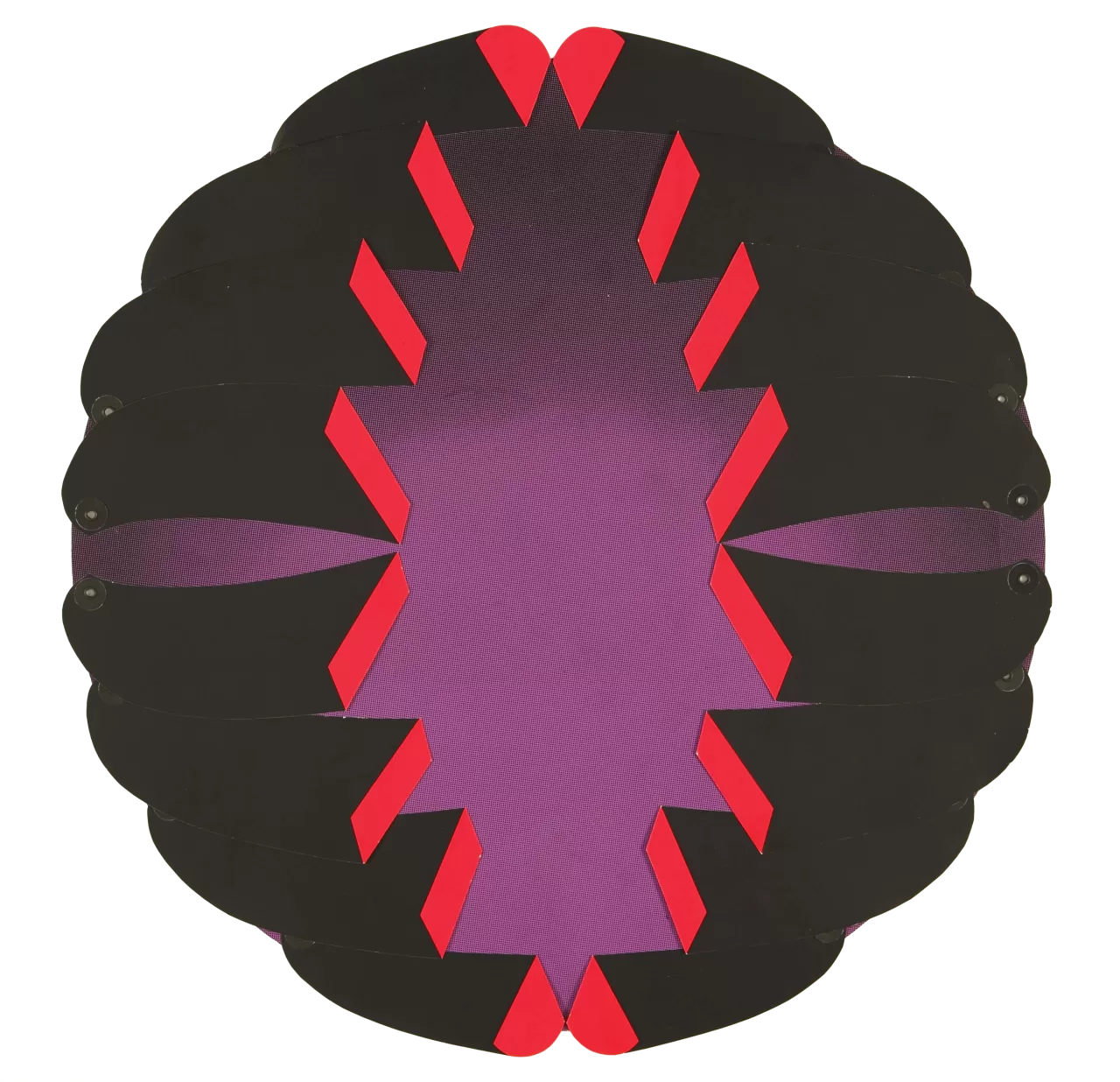

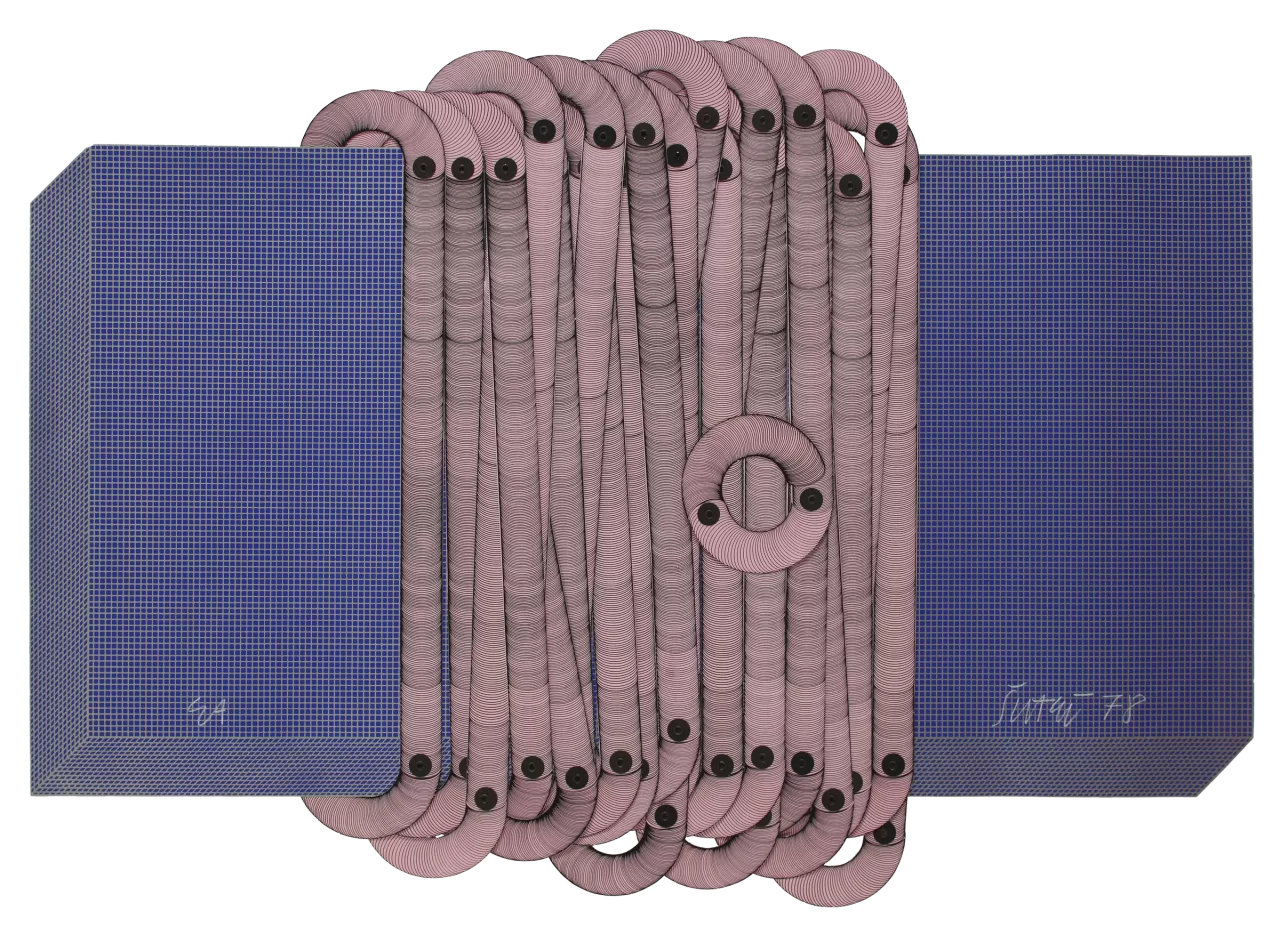

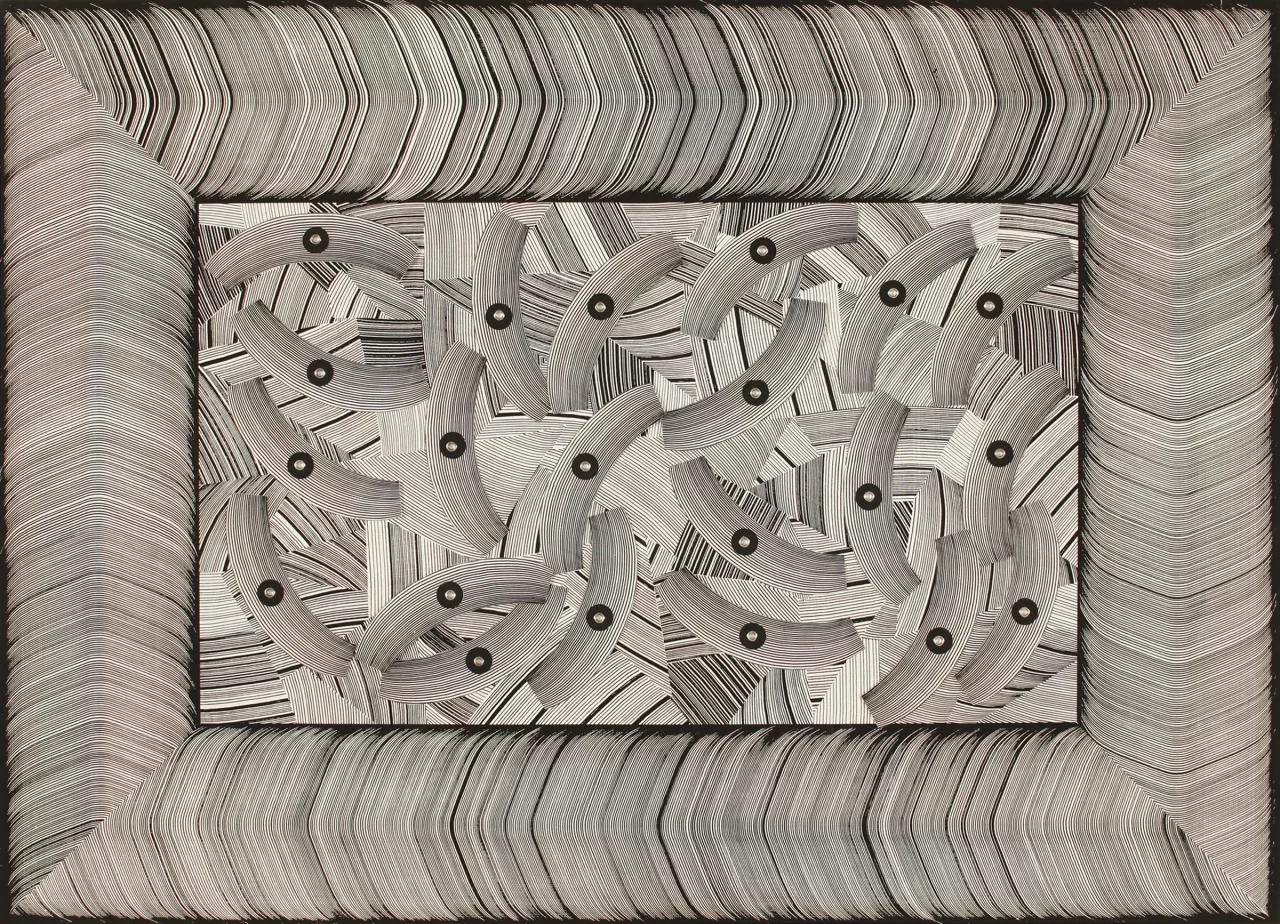

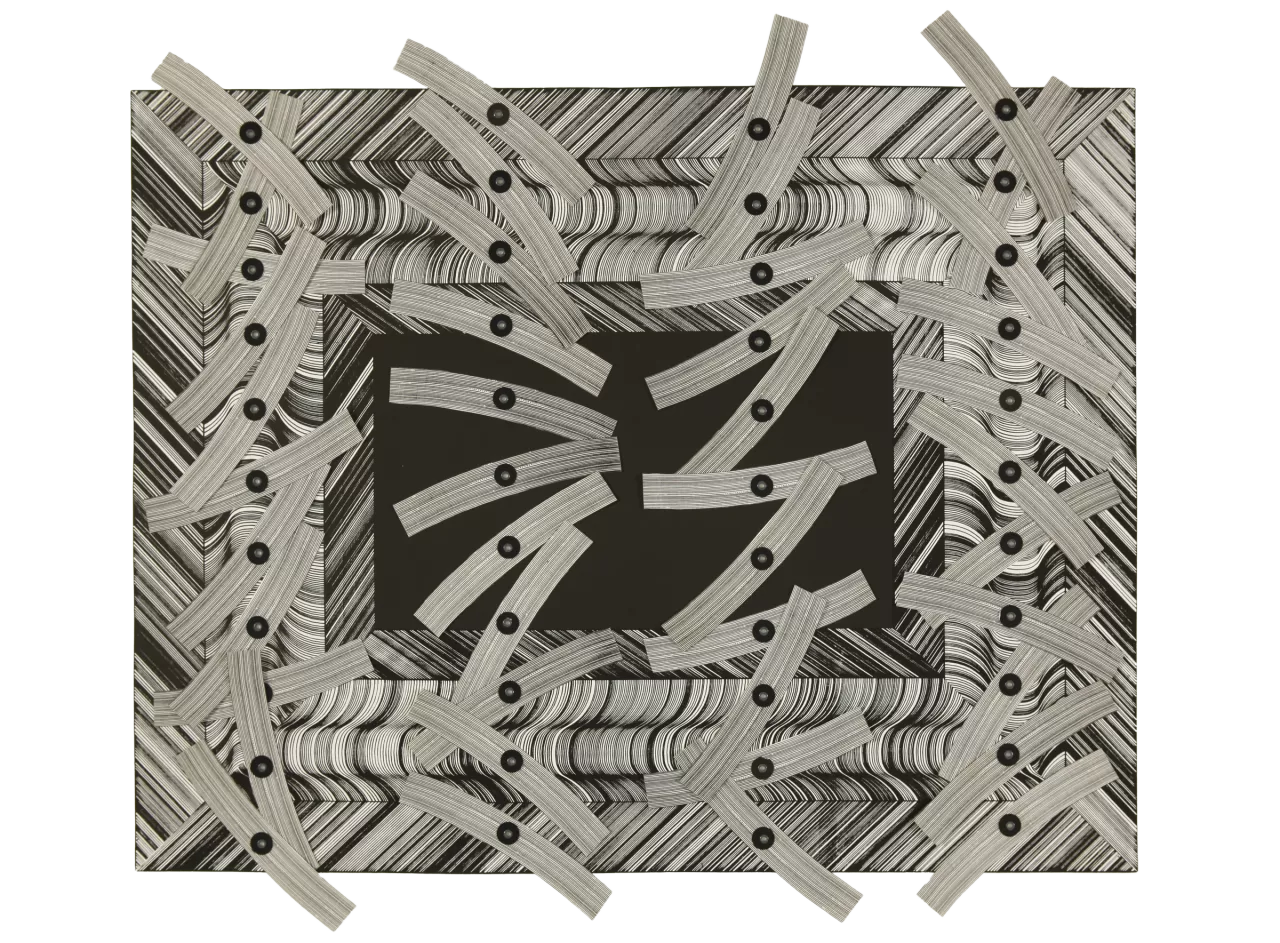

Furthermore, in the early seventies, in addition to colour, Šutej expanded and explored the compositional possibilities of this type in the black and white contrast as well, thus returning to the achromatic value of his earlier pieces (Cavallino I, Cavallino III). In this period, while developing complex forms and variations, the artist established the new complex-reductive compositional type whose basis (the carrier of mobile elements) is curtailed and reduced to minimal surfaces, with the growing complexity of mobile elements (SM 10, Black and White, The Big Black, Green and Red Print, Brown and Blue, 76/III). Using the same elements, inspired by the mid-seventies folklore material, he introduced new visual forms into his graphic art based on the aspect of micro-fibre linear structures and elongated yarn forms (Print 74/I).

In the late seventies, again under the aegis of the basic compositional type, in his mobiles Šutej explored the effects and possibilities of reduced motion and colour scheme, developing them until the mid-seventies. In these works, the basis as the carrier of mobile elements is also the carrier of the visual representation where the arms and the movable components are less present in number and size, only as a visual upgrade featuring new visual variations, but without dramatic permutations (Blue Print, Print 78/III, Print 79/III, Brown Print, Black Cube, Picture at an Exhibition 3, Picture at an Exhibition 4, Picture at an Exhibition).

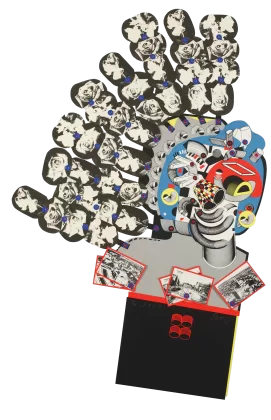

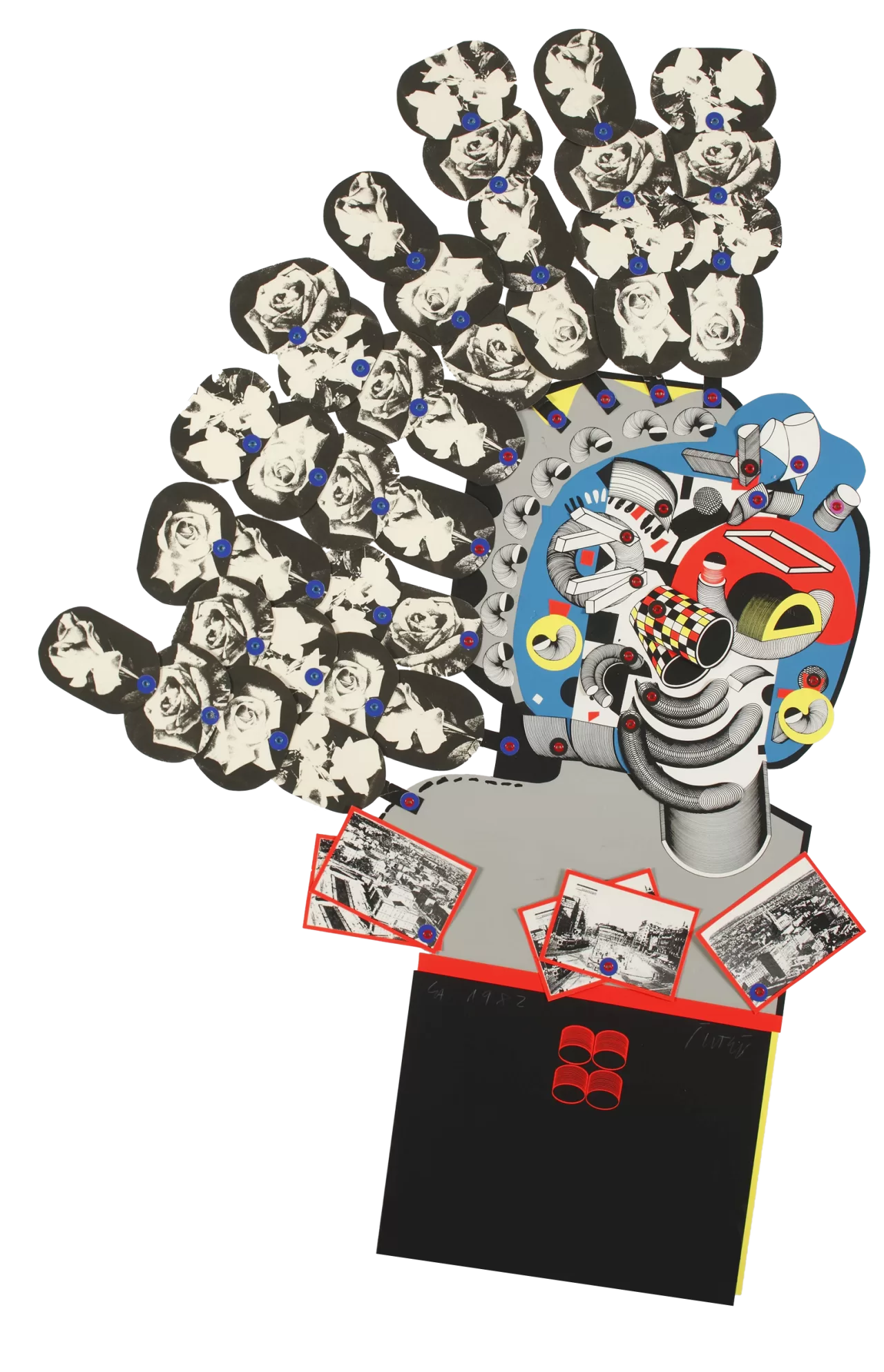

In the early eighties (1982-1983), along the lines of the basic compositional type, Šutej established the figurative composition type as an innovative typological novelty based on objective association where a character (human or animal) emerges from a visual bounty of integrated geometric and abstract forms applied onto a surface in the form of a figurative outline, whose humorous associative iconism is highlighted by readymade elements; in the case of Apollo from Zagreb these are postcards from Zagreb and flower garlands.

Parallel to the mobile serigraphs, in the same creative period Šutej made drawings and traditional prints, like Irregular Ball, Carain and Segnapassi Print, which often served as the initial ideas he later drew elements from for further elaborations of his mobile serigraphs models, such as Green Ball, Picture at an Exhibition 3 and Green and Red Print. By constantly renewing and expanding his own postulates and artistic concepts, Šutej brought mobile serigraphy to its peak, exhausting all of its possibilities in the process.

Varying between the solutions on the issues of space, motion and openness – present from the very beginning, Miroslav Šutej gained prominence as an author of creative syntheses based on opposites. His originality and innovativeness lie in creating new formations by way of open consideration, a free approach to the medium and the introduction of new procedures. Absorbing the new artistic atmosphere and assimilating current contemporary art theories and tendencies, he freed himself from the norms and limitations of the medium and surpassed the two-dimensionality and stasis of the surface and the work itself. Reconciling personal inclinations and the experiences of his time at a very early stage, he evolved into one of the pioneers of optical art and an author who expanded the experience of multi-original art. In the words of Zvonko Maković, Šutej “managed to give a particular measure to the issues of entire contemporary art, putting them into an entirely new environment and giving a different sign to both the environment and the work“ [26]. His versatile and diverse body of work, with print as the dominant medium, was in its entirety not only Šutej’s response to the challenges of the times, but also a challenge to the times.

Ana Petković Basletić

[1] Ješa Denegri, EXAT 51; Nove tendencije: umjetnost konstruktivnog pristupa, Zagreb: Horetzky, 2000, 474.

[2] Ive Šimat Banov, “Miroslav Šutej (1936-2005), ime za novu fiziku i ludičku mehaniku” in: Grafika, 7 – 8, 2005, 30. Igor Zidić in 1962, ahead of Šutej’s first solo exhibition, highlighted a detachment from the absolute order of geometric abstraction: “turned off-the-rack qualities of geometry into fantasy”. Igor Zidić, Tkalac na propuhu, Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, 1972, 6.

[3] See more in: Ješa Denegri, Apstraktna umjetnost u Hrvatskoj 2, Split: Logos, 1985, 61–68; and Slavica Marković, Zagrebačka serigrafija, exhibition catalogue, Zagreb: Department of Prints and Drawings, Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, 2018.

[4] See more in: Vera Horvat Pintarić, “Ikonika i optika Miroslava Šuteja” in: Kritika i eseji, Zagreb: Glyptotheque, Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, and EPH, 2012a, 214.

[5] See more in: Denegri, 1985, and Denegri, 2000.

[6] For Šutej’s early works, see more in the monographic editions: Tonko Maroević, Šutej / Crteži iz obiteljskog dvorišta, Zagreb: Department of Prints and Drawings, Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, and Šutej Foundation, 2009, and Slavica Marković, Zvonko Maković, Miroslav Šutej: mobilne serigrafije, Zagreb: Department of Prints and Drawings, Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, 2015.

[7] See more in: Vera Horvat Pintarić, “Suvremena jugoslavenska umjetnost” in: Kritike i eseji, Zagreb: Glyptotheque, Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, and EPH Media, 2012, 203–210.

[8] Denegri, 1985, 22.

[9] Zvonko Maković, “Miroslav Šutej” in Život umjetnosti, 22-23, 1975, 92.

[10] See more in: Horvat Pintarić, 2012a, 214–217.

[11] Tonko Maroević and Zvonko Maković, Miroslav Šutej: prekrivene oči, exhibition catalogue, Zagreb: Art Pavilion, 2004.

[12] Vera Horvat Pintarić, “Slika objekt Miroslava Šuteja” in: Kritike i eseji, Zagreb: Glyptotheque, Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, and EPH Media, 2012c, 398.

[13] Bombardment of the Optic Nerve, I, 1963, tempera and pencil on paper, MoMA, inv. no. 373.1965. After said exhibition between 23 February and 25 April 1965, the piece was acquired for the MoMA in New York City, where it is still kept, along with several other of Šutej’s prints.

[14] See more in: Horvat Pintarić, 2012c, 398-399.

[15] Maković, 1975, 96.

[16] See more in: Denegri, 1985, and Denegri, 2000.

[17] See more in Radovan Ivančević, “Mobilne multikompozicije grafike Miroslava Šuteja” in: Život umjetnosti, 54–55, 1993, 64–69.

[18] Ive Šimat Banov, 2005, 32.

[19] The book Opera aperta (1962) by Umberto Eco was translated and published in Yugoslavia in 1965 and has made a significant impact on the development of art and literature theories.

[20] Zvonko Maković: “Grafika Miroslava Šuteja,” in: Miroslav Šutej / Mobilne serigrafije, Zagreb: Department of Prints and Drawings, Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, 2015, 37.

[21] Slavica Marković: “Miroslav Šutej / mobilnost u znaku,” in: Miroslav Šutej / Mobilne serigrafije, Zagreb: Department of Prints and Drawings, Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, 2015, 21.

[22] Vera Horvat Pintarić, “Mobilna grafika Miroslava Šuteja” in: Kritike i eseji, Zagreb: Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Glyptotheque and EPH Media, 2012d, 296.

[23] Ivančević, 1993, 64.

[24] After 1985 Šutej still made graphic mobiles, but in other graphic techniques, as well as serigraphs that are not mobiles, which is why these works are not included in the scope of this exhibition.

[25] See more in: Marković, 2015, 23-24.

[26] Zvonko Maković, 1975, 92.